Detroit: America’s Rising Phoenix

Gallery

When I was younger, I would hardly go downtown. Maybe with my parents for a rare visit to the Eastern Market, or with my grandmother to go see a show at the Fisher, but nothing too venturous. As I’ve gotten older I’ve had many different experiences in Detroit and most of them have been overwhelmingly positive and fantastic. For example, I adore going to the Detroit Institute of Arts. I could go with some friends or alone just to clear my head. I almost always go to sit in Rivera Court and I enjoy walking around in European and Renaissance art. I’m always downtown for the plays and musicals that come to town. The Fisher, the Fox, and the Detroit Opera House are like time capsules that I just can’t get enough of when I walk through the doors. Recently I was given the opportunity to walk through the Heidelberg Project, which was extremely powerful in its own way, it just further emphasizes the power of art. I’ve seen the urban farming that goes on in the city, rebuilding the sense of community and self-empowerment that has been so desperately missed. I finally got to go inside the Guardian Building. At one time that building was used as a fully functioning banking hall and now is a beautiful reminder of the great architects who built amazing structures in Detroit.

Hart Plaza and the Riverfront are my other favorite places to be. The Riverfront is a place where many can gather and watch the Detroit River, steady and strong, flowing by. Hart Plaza also has a statue of the man who founded Detroit, Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac. The marker, which can be read in English and French, tells of Cadillac sailing down “de Troit,” or the “the strait,” with his 75 canoes in July of 1701. He sailed from his camp, not far from present day Grosse Ile, back up the river to find a spot that pleased him enough to claim for France. As the marker tells, he found that spot “on the shore near the present intersection of West Jefferson and Shelby” because it was high enough above water level and was a valuable strategic placement for a fortress that could theoretically control the entrance and distribution of anything to the Great Lakes region. From there, the aptly named settlement of Fort Pontchartrain du Detroit grew from about an acre of land surrounded by “fifteen-foot oak pickets” to the haunting metropolis that today’s world calls “The Motor City.”

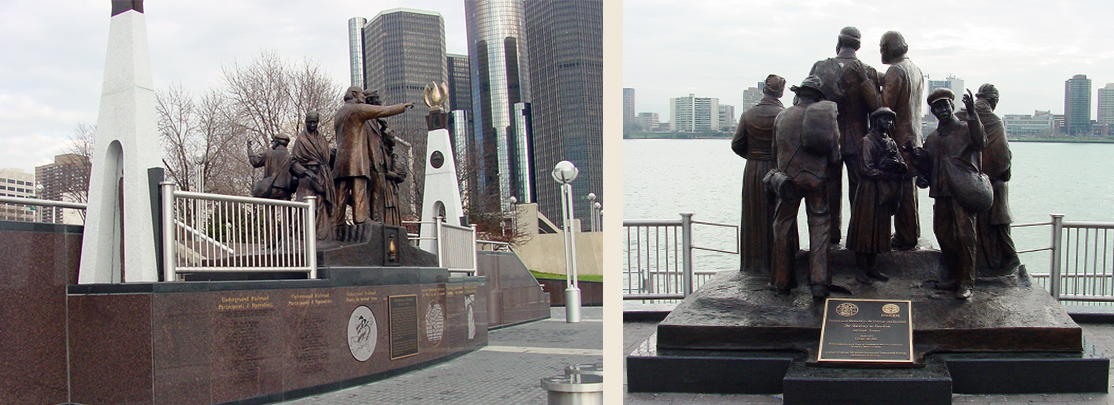

Also in the plaza, by the river’s edge, is a monument dedicated to the Underground Railroad, a secret network used in the 1800s to help escaped slaves get away from their southern plantation owners and hopefully one day find their freedom in Canada. The monument shows the secret paths that the slaves used as well as the hidden stops that offered refuge to slaves. The Fugitive Slave Act, passed in 1850, meant anyone caught harboring a fugitive slave would be punished and the slave would be sent back to his or her “master.”

Underground Railroad “conductors” were people who gave any kind of aid, typically monetary, spiritual, or material, to the runaway slaves. According to the Detroit Historical Society’s “Encyclopedia of Detroit,” Detroit had strong willed individuals ready to defy the Fugitive Slave Act by providing food and places to sleep. One of Detroit’s most notable contributors to the Underground Railroad was George de Baptiste. Baptiste was born free in Virginia and decided to move to Detroit later in his life. He was a clever man, who, along with his barber shop and bakery, eventually owned a steamship called the T. Whitney, which he used to secretly take slaves from Detroit to Canada. His church, Detroit’s Second Baptist Church, had the first black congregation in Michigan and it was a major stop in the Underground Railroad. Leaders of the church worked with major names in the abolitionist movement, such as Sojourner Truth and Frederick Douglass. For over 30 years the church “housed an estimated 5,000 fugitives.”

I contemplate this remarkable history as I view the water, so calming and mysterious. The river never stops moving; you never see the same wave twice. Just like the city itself. I love watching the passing freighters and boats go by, occasionally catching a sunrise or sunset, while walking along the skyline of the city. It might take more time than other places, and more trial and error. Weeds may cover forgotten and once majestic ruins, historic neighborhoods may get abandoned and blighted, but Detroit is rising.

Nationally, Detroit is again becoming the place to be. Tourists are no longer asking if it’s safe, they are taking the next flight to get here.

Even with the renewed interest in Detroit, it’s important to know about the past of the city and our connection to it. Do some research on your own. It’s history reveals examples of surprising heroism, like George de Baptiste. Most importantly, learn the history of the people, the ones who have a never say die spirit and who have their own stories to tell if we are willing to listen.

I listen to the river. It’s the same river that brought Cadillac here to colonize the land, but that river also served to help escaped slaves. The river helped the city recover when it burned to the ground in 1805 but the people rebuilt it. As evidence, the city’s flag says in Latin, “It will rise from the ashes.”