DREAMers at HFC Wait for Congress to Act

Gallery

In 2001, Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) introduced to the Senate the Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors (DREAM) Act, a bill which if passed into law would institute a workable process for establishing the immigration status of children of undocumented immigrants brought into the United States as minors. Despite having 18 bipartisan cosponsors, the bill fell short of the 60 votes necessary to move forward.

Over the past 16 years, bipartisan support for efforts to put in place legislation that would shield these young undocumented immigrants, or DREAMers, from deportation has grown and several versions of the DREAM Act have been introduced both as stand-alone bills or as part of more comprehensive legislation.

In 2012, to provide a temporary reprieve for DREAMers pending a viable solution from Congress through an executive order signed by President Obama, the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program was created. For renewable periods of two years, DACA shielded DREAMers who qualified for the program from deportation and granted them permission to work, study and even obtain driver’s licenses.

To be eligible for DACA, applicants had to have proof that they were younger than 31 years old on the day the program began; had to have arrived in the country before they were 16 years old; and they had to have lived in the United States continuously beginning on June 15, 2007. Eligible applicants also had to maintain a clean criminal record and either be enrolled in high school or college, or be serving in the military.

On Sept. 5, 2017, Atty. Gen. Jeff Sessions announced that the Trump administration would discontinue the DACA program. Congress has been given six months to pass legislation that will determine the immigration status of DREAMers. The White House said no new applications would be accepted after Sept. 5. Those whose permits would expire before March 5, 2018, could apply for renewal. Following this announcement, the Department of Homeland Security indicated that they will continue to exercise discretionary authority in denying new permits or terminating previously issued ones, giving no guarantee that new permits would be issued or that previously issued permits would be renewed.

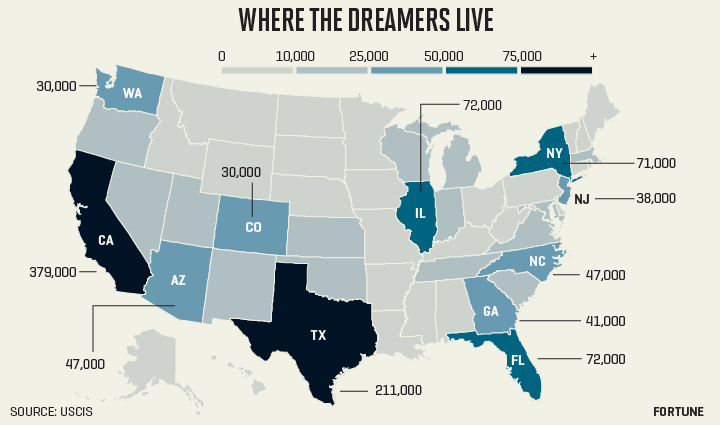

News of the discontinuation of DACA has evoked great public outcry. The 800,000 DREAMers who have signed up for the program, and numerous others who were planning to, now live in fear of deportation from a country they know as their home.

According to data from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, 78.5 percent of those who had previously signed up for DACA are of Mexican origin.

Milady Vergara is a senior at Henry Ford College. Her parents are originally from Mexico. She recently submitted her first DACA application. She now lives in fear.

“The phasing out of DACA has brought a lot to my mind. Questions such as how will I actually achieve my goals, what alternatives will I have to take, what will become of my family and I?” she says.

Vergara is 17 years old and is the oldest of five children in a household of seven.

“I have lived in America for 15 years. My journey into the country is something I can’t remember. I don’t remember my life before coming here either. Living in this country is all I know,” she says.

“Even though I have lived in America pretty much my entire life, Yo soy orgullosamente Mexicana (I am proudly Mexican),” Vergara adds. “My family has maintained contact with the rest of our family in Mexico.”

“My parents risked their lives to come to the U.S so that my siblings and I can have a good life. It would not have been possible if we were in our homeland,” Vergara says.

“I am majoring in nursing because I believe my life can end at any time or place but for the time being I want to help expand the lives of others for as long as I can. DACA means being able to achieve these goals and dreams I have set for my life and being able to support my family.”

Vergara hopes Congress acknowledges that DREAMers are as much a part of this country as their peers who were born here. She also hopes that they come up a with a solution that will work in favor of DREAMers. If things don’t work out as she hopes, Vergara will keep fighting to make it clear that her being here is not a threat to anyone.”

“If I had a minute to address the President of the United States or Congress on behalf of my fellow DREAMers, [I] would tell them how much we want to keep our position in the U.S that we have earned, for ourselves and our families. I would let them know that we will keep fighting to get back what [was] taken from us,” Vergara says.

Brenda Angulo-Villa is a sophomore at HFC majoring in Business Management. She has been a DACA recipient for two years and recently renewed her permit for another two years. Brenda’s parents are originally from San Ignacio, a small town in Jalisco, Mexico. They both came from a humble background. Her father dropped out of school when he was seven years old to help support his mother and six siblings after his father died. Her mother was six years old when she and her 12 siblings were left to fend for themselves after their mother died and their father remarried.

Angulo-Villa was born in Mexico. Her two siblings were born in the U.S. She came to this country before she turned two.

“My family and I have been living in the United States for approximately 17 years. [..] I was too little to remember my dangerous journey here,” Angulo-Villa said.

“My parents have taught us the importance of staying connected to our roots. We often make phone calls to Mexico to speak to aunts and uncles that still live there. During the month of December, my siblings travel to our hometown,” she adds. “I identify myself as Mexican. My nationality is something I will always be proud of regardless of who is disturbed by it.”

“When I first heard about DACA being phased out, I was furious. It will not affect my siblings but as for me, I feel that I am in danger of losing everything I have worked for. I fear being deported. I fear not being able to go to school. I fear not being able to work. I fear not being able to have a license. Most of all, I fear for the rest of the DREAMers,”Angulo-Villa says.

“As much as Trump’s decision infuriates me, I have remained calm. I am optimistic that Congress will realize that it is inhumane. I have just renewed my permit so it will be valid for another two years. My mom recently became a resident and applied for my residency too. By the time my DACA permit expires, hopefully I will be a resident of the United States. Whatever the case, I will continue to advocate for all DREAMers.” Angulo-Villa says.

“If I could speak to Trump, I would ask for him to tell me how DREAMers disturb him or the economy. We pay for our permits and pay taxes but do not get help when it comes to medical insurance or financial aid for school. His father was the son of immigrants, his mother was an immigrant and so is his wife. What is the issue? We do not take away anything from U.S citizens. We work hard just like our parents to realize our dreams.”

Prior to the announcement of the discontinuation of the DACA program, in a bipartisan effort, on July 20, Sens. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.), Dick Durbin (D-Ill.), Jeff Flake (R-Ariz.), and Chuck Schumer (D-NY) introduced the DREAM Act of 2017. If the bill is passed into law, it would provide undocumented immigrants, those with temporary protected status, and DACA recipients who graduate from U.S. high schools, attend college, enter the workforce, or enlist in a military program a direct path to citizenship.