Mirror Neurons

Gallery

You’re sitting in a lecture on a Tuesday afternoon. Three rows ahead, someone lets out a massive yawn. Within seconds, your jaw stretches wide. You weren’t tired; at least, you weren’t five seconds ago. Or picture this: you’re working on a design project with classmates when your teammate starts nervously bouncing their leg. Suddenly, your own leg won’t stop moving either. You’re not even aware you’re doing it.

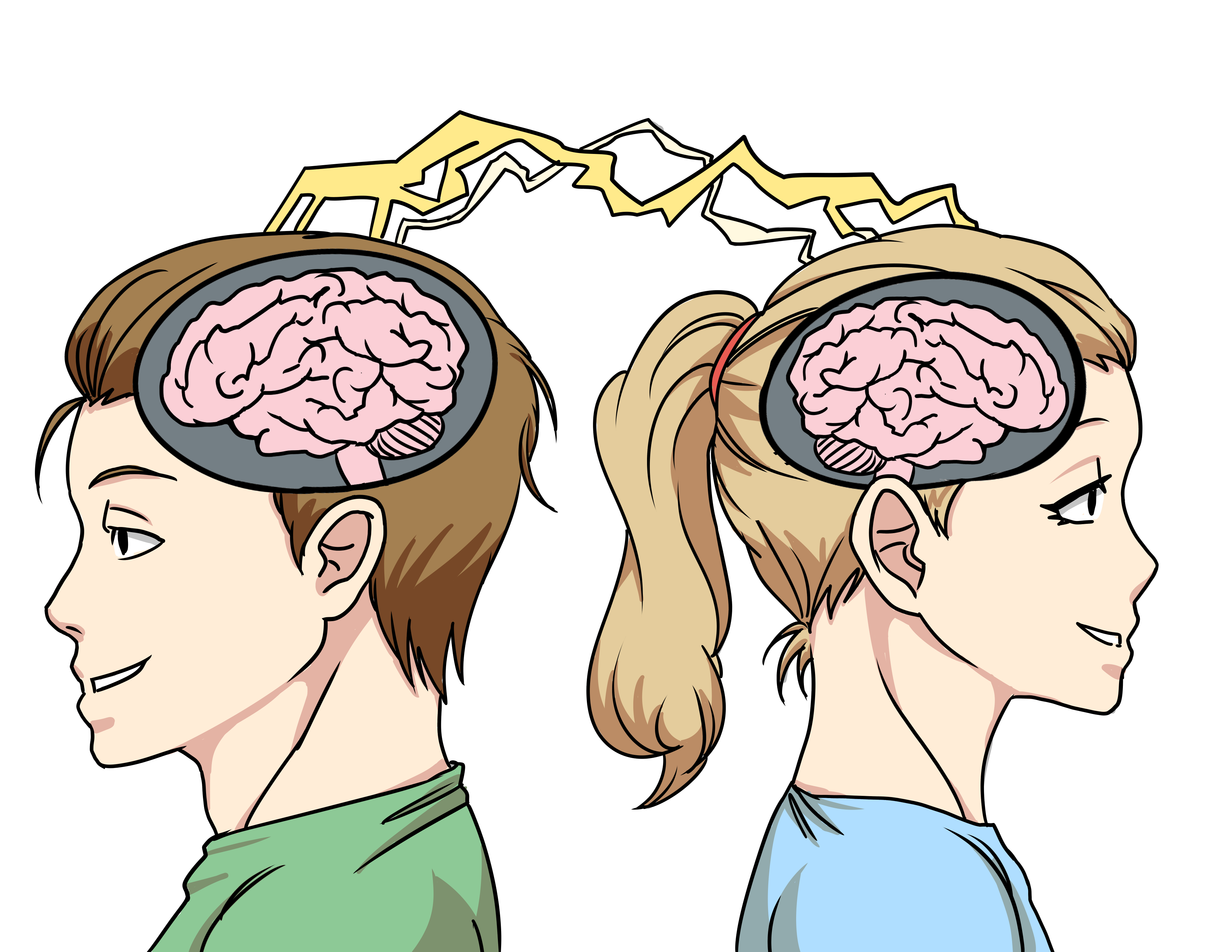

These moments seem small, almost automatic. But they reveal something profound about how your brain actually works. Your brain isn’t just a camera passively recording what’s happening around you. When you watch someone do something, your brain runs a secret simulation of that same action, like you’re doing it yourself. This invisible phenomenon has a name: mirror neurons.

Mirror neurons are brain cells with an unusual job. They fire in two situations: first, when you perform an action yourself, and second, when you watch someone else perform that same action. If you reach for your coffee cup, certain motor regions in your brain light up. But here’s the interesting part: if you watch a friend reach for their cup across the table, many of those same regions activate again, as if you were doing it yourself.

This mirroring mainly happens in areas of your brain responsible for planning and controlling movement, such as the premotor cortex and parts of the parietal lobe. But it’s not just about physical actions. Your brain also mirrors facial expressions and emotions. Scientists discovered this phenomenon in the 1990s when studying macaque monkeys. They noticed that the same neurons fired whether a monkey grasped food or simply watched another monkey do it. Since then, we’ve learned that humans have an even more sophisticated mirror neuron system.

The real significance? Mirror neurons are the foundation of empathy, understanding, and our ability to learn from one another. They’re why you can feel what others feel without them saying a word.

Think about learning a skill like observing a lab partner carefully pipette a solution, a friend showing you a cooking technique, or someone demonstrating a gym exercise. Have you ever learned how to navigate campus bureaucracy just by watching someone else do it first? You watch, and something clicks. Your brain is doing more than just storing visual information. Your mirror neuron system is translating what you observe into patterns your motor system can use later. This automatic mirroring helps explain why watching someone practice a skill makes it easier to learn that skill yourself. Research consistently shows that people do better when they learn by watching a real human demonstrate something than by following instructions on a screen or looking at arrows in a manual. A stronger activity in your mirror-related brain regions happens when the model is a real person. Your brain is wired to learn from people, not just from instructions.

This is why a passionate professor explaining their research makes the material stick more than reading the same information in a textbook. It’s not just the information itself. Your mirror neurons are encoding not just the information but the way of being around that information. They’re picking up their enthusiasm, their way of thinking about the subject, their entire approach. You’re not just learning facts. You’re learning a way of being around those facts. This explains why you might randomly discover your major by sitting in an amazing lecture or spending time around friends who are genuinely excited about a particular field. Your brain was mirroring their energy and engagement, simulating what it felt like to care about that subject the way they do.

Now imagine walking into a study room right before midterms. Shoulders are tense, eyes are wide, and the energy is tight and anxious. You walk in calm, but within minutes, your heart rate creeps up, and your to-do list starts spiraling through your mind. What happened? Your mirror neurons happened.

Emotions are contagious in a literal, biological sense. When you see someone’s stressed facial expression or tense body posture, your brain partially recreates that state in your own circuits. This isn’t just psychology. It’s neurology. The same brain regions that activate when you feel anxiety activate when you observe someone else feeling it. Over time, repeated exposure to certain emotional climates doesn’t just affect how you feel that day. It shapes what your brain expects and how you naturally tend to react. Research on social influence reveals a captivating pattern: have you ever laughed at something that wasn’t actually funny, just because everyone else was laughing? That’s not you being fake or going along with the crowd. That’s mirror neurons hijacking your sense of humor without your permission. Someone cracks a mediocre joke, their face shows they think it’s hilarious, and your mirror neurons go “oh, we’re laughing now” before you even process whether it was funny. Your brain literally can’t help itself. It’s involuntary neural peer pressure. You’re not choosing to laugh; your brain is choosing for you based on what it sees in the room. You’re fundamentally a biological laugh-track that came with a consciousness.

Think about the people in your life. That one friend who’s perpetually pessimistic, always predicting failure in group projects? Everyone around them is mirroring their stressed tone, posture, and expressions. Slowly, the whole team’s motivation drains. On the flip side, the roommate who celebrates small wins and laughs easily creates a different effect. They lift the mood of everyone nearby, especially during stressful situations. Their optimism spreads, neuron by neuron.

A teacher’s genuine enthusiasm works the same way. It literally infects students, making even dry topics feel more engaging. But chronic boredom at the front of the room spreads just as fast. Your brain is constantly absorbing the emotional climate around you, not through willpower or conscious choice, but through the automatic work of your mirror neuron system.

So, what exactly is empathy in neuroscientific terms? It’s not just a nice feeling or a moral choice. It’s your nervous system running a light version of someone else’s internal experience. When you see a friend’s eyes well up with tears, your brain doesn’t just intellectually understand their sadness; your own brain is partially experiencing it. Brain-imaging studies show that regions involved in both feeling emotions yourself and observing emotions in others activate when you watch someone suffer.

This is why sitting with a friend who’s hurting can be healing. The boundary between “your” emotional state and “their” emotional state is much blurrier than most people realize. You’re not separate from the people around you. You’re connected to them through these invisible neural networks.

This doesn’t mean mirror neurons explain everything about empathy. The science is more nuanced than that. Empathy also relies on higher-level thinking, like understanding diverse perspectives and past experiences. But mirror neurons help explain why empathy can feel so immediate and physical, why you feel it in your body before you think about it in your mind. Every small action you take sends a pattern into the social world around you.

Every smile exchanged with a stranger in the hallway carries more weight than we often realize. Think back to a moment when you felt unseen, and someone offered you a simple, genuine smile. Before you were even fully aware of it, your mirror neurons responded. Subtle motor and emotional circuits activated, your face prepared to smile back, and your body chemistry shifted just enough to make the world feel less heavy. That single interaction shaped your internal state, and later, when you encountered someone who seemed to be struggling, the warmth in your own expression came more naturally.

The moments that truly influence us are often small and quiet. They are not usually grand speeches or dramatic conversations. Instead, they are the understated exchanges, such as a professor who shows genuine interest in your ideas or a friend who stays hopeful when everything feels overwhelming. These experiences matter because they deeply engage your mirror neuron system.

This is not sentimentality. It is neuroscience. One person’s choice can ripple through another person’s mind, neuron by neuron.

This connects to a familiar phrase: “Be the change you want to see in the world.” It may sound idealistic, but mirror neurons provide a biological foundation for this idea.

Your behavior is not simply a private action. It becomes a signal that other people’s brains continuously read and reflect. Each time you remain calm in a tense situation, listen instead of interrupting, or show visible excitement about learning something new, you introduce patterns into the environment that others will naturally mirror.

Your classmates’ nervous systems are responding to your cues, just as yours responds to theirs. You are all part of an invisible network of shared emotions and reflected behaviors. Change is not only about good intentions. It is about consistent, observable actions that other brains can simulate and gradually adopt.

The neurons firing in your brain when you watch someone else are the same neurons that will fire in their brain when they watch you. That’s the biological connection between all of us. That’s how influence works at the level of our brains. You are not separate from the world around you. You are part of a connected network where your choices ripple outward in ways you may never fully see, but that your mirror neurons ensure will be felt. When you choose kindness, when you choose to stay hopeful, when you choose to smile at someone having a rough day, you’re not just being nice. You’re participating in an act of invisible communication that travels from brain to brain, changing neural patterns in ways that no one fully sees but that everyone feels.

The next time you catch yourself yawning after someone else yawns, or feeling hopeful after talking with an optimistic friend, or mirroring that nervous leg bounce during class, remember what’s happening. Your mirror system is linking you to other people. And every small choice you make sends that invisible pattern outward. In the most real, neurobiological sense possible, you’re connected to everyone around you. And you have the power to shape what that connection feels like.