A Look Back at the History of Father Coughlin

Gallery

On Sunday evenings throughout the 1930s, millions of Catholic families would gather around their radios, captivated by the voice of Father Coughlin—mellow, magnetic, and commanding. His broadcasts echoed across the nation: “When we get through with the Jews of America,” he once said, “they’ll think the treatment they received in Germany was nothing.”

Coughlin, dubbed the “Radio Priest,” did not consider himself an antisemite. In fact, he saw himself as a democrat, a radical, and an anti-communist. He blurred the lines between politics and religion, paving the way for modern day televangelists and politicians.

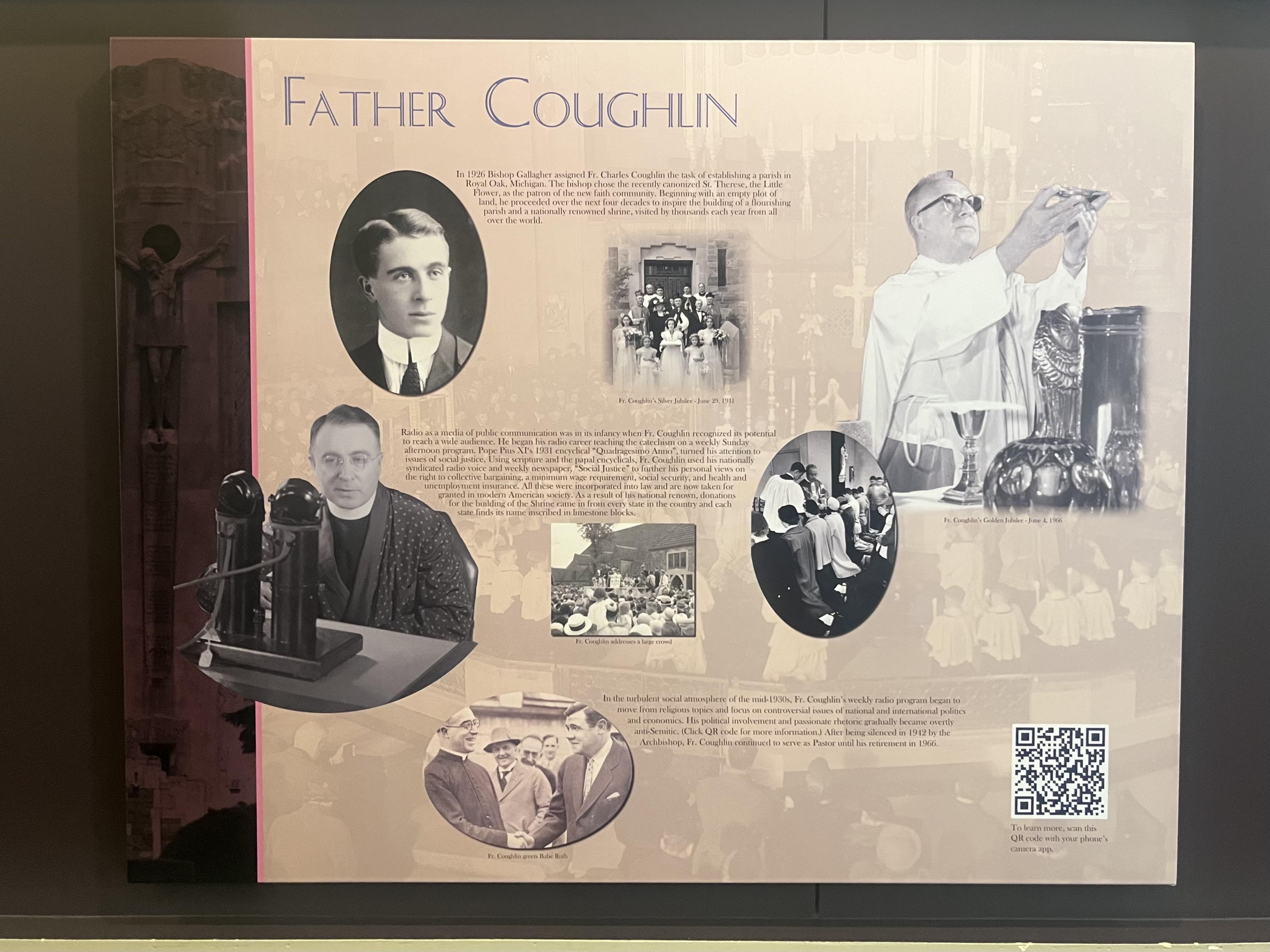

Charles Coughlin was born into a devout Irish-Catholic family in Hamilton, Ontario, in 1891. As a young man, Coughlin was drawn to both politics and priesthood, but decided to commit to a life of ministry. He attended St. Basil’s Seminary in Toronto and was ordained as a priest in 1916. Ten years later, he was assigned to The Shrine of the Little Flower in Royal Oak, Michigan. The Archdiocese of Detroit authorized him to construct the church, and the Charity Crucifixion Tower—completed in 1931—was built as a response to the anti-Catholic Klu Klux Klan burning a cross in front of the church shortly after it opened. Originally intended to serve a congregation of around 25 people, the church quickly grew along with Coughlin’s popularity, especially when he offered the first Catholic radio broadcast in 1926.

Coughlin’s radio show, “The Golden Hour of the Little Flower,” began with sermons and catechism. It was intended to draw more members as well as raise money to fund the church. The broadcast was revolutionary for the time, as Coughlin was one of the first public figures to utilize the radio to shape public opinion. Radio was the dominant form of entertainment and information, and during the depths of the Great Depression, many Americans were searching for answers to their financial and social struggles. The program was picked up by CBS, and its popularity skyrocketed, garnering over 30 million listeners and becoming one of most listened-to radio broadcasts in the United States.

By the 1932 presidential election, “The Golden Hour of the Little Flower” had evolved into a political platform. Coughlin championed Franklin Roosevelt, stating the fate of America was “Roosevelt or ruin.” Roosevelt’s policies aligned with Coughlins’ ideas on monetary reform, and the two formed a close relationship, frequently meeting.

As Coughlin’s influence grew, so did his criticisms of powerful institutions such as Wall Street bankers. After Roosevelt was sworn into office, Coughlin’s basement was bombed in the middle of the night. He told The New York Times the bombing was “an act of intimidation” aimed at silencing him and his broadcast.

Despite their early alliance, the relationship between Coughlin and Roosevelt soon soured. Coughlin accused Roosevelt of failing to live up to his promise to “drive the money changers from the temple.” He began to publicly denounce Roosevelt and the New Deal, branding him “Franklin Double-Crossing Roosevelt.”

The break with Roosevelt propelled Coughlin deeper into controversy, marking the beginning of his descent into radicalism. He formed the National Union for Social Justice (NUSJ) and began a weekly magazine, “Social Justice.” Through these platforms, Coughlin spewed antisemitic conspiracy theories, accusing Jews of orchestrating Marxist plots against America. After Kristallnacht—the November 10, 1938, Nazi attack on Jews—Coughlin blamed the Jewish victims for their persecution, justifying the violence. While U.S. media refused to air his broadcasts, Nazi Germany embraced his message. A New York Times correspondent in Germany even called Coughlin “the hero of Nazi Germany” and others began to call his church “The Shrine of the Little Führer.”

Coughlin’s ideology blended Catholicism with radical political views, fueling antisemitism, nationalism, and authoritarianism. His ability to create an “enemy”—whether it be Jews, communists, or elites—allowed him to channel widespread fear and frustration to his audience. This tactic not only solidified his influence but resembled those of authoritarian leaders of the same era such as Hitler and Mussolini, whom Coughlin often quoted.

Despite mounting criticism, Coughlin retained a loyal audience. His broadcasts continued to spread hateful rhetoric, including claims that Jews had planned the war for their own profit and to involve the United States. Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, The U.S. government denied him a passport due to his “reported pro-Nazi” views, and in 1942, the FBI raided his church. That same year, on May 1, Archbishop Edward Mooney ordered Coughlin to stop all non-pastoral activities. Under the pressure and the threat of being defrocked, Coughlin’s broadcasts and publications ceased.

Though silenced on air and in print, Father Coughlin remained the parish Priest of the Shrine of the Little Flower until his retirement in 1966. As one of the most influential men of his time, his ability to weaponize fear, spread misinformation, and sow division set a modern-day precedent for the manipulation of the media to further one’s agenda. Father Coughlin’s legacy—both captivating and controversial—forever altered the intersection of religion, politics, and public opinion.