Parasite: A Look Inside the Feverish Insanity of Class Warfare

Gallery

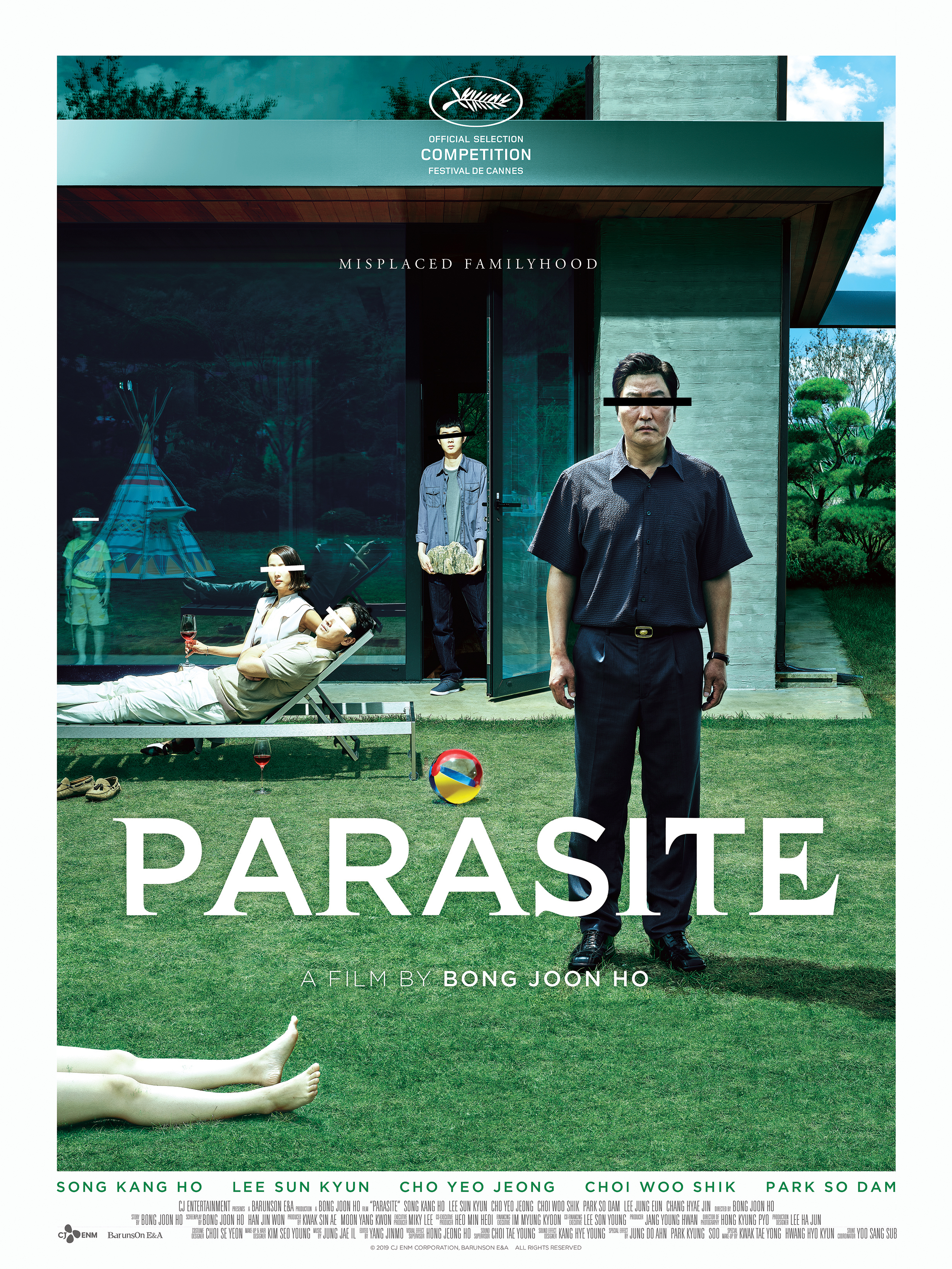

“Act like you own the place.” So reads the tagline of “Parasite,” the newest film from one of South Korea’s most acclaimed filmmakers, Bong Joon-Ho. Known for his repertoire of darkly comedic and edgy films, Bong has received international recognition from past efforts such as “Memories of Murder,” “Snowpiercer,” and most recently, “Okja.”

With “Parasite,” Bong treads familiar stylistic ground and scales new thematic heights as he presents the story of the impoverished Kim family, who spend their days trying to make ends meet by folding cardboard pizza boxes in their cramped and oppressive basement apartment. When Ki-Woo, the son (Choi Woo-shik), is presented with the opportunity to tutor the teenage daughter of the exceedingly wealthy Park family, he finds himself in an alien world of the wealthy family’s modernist mansion, luxury cars, dutiful servants, and pets that have been pampered and fed more than he ever has in his life. Transfixed, Ki-Woo develops a mischievous plan to replace every single servant of the Kim family with members of his own, enabling them to finally live what they believe to be a life of luxury. Thus, the Kims commence a strange and manipulative game that tests just how far they can take advantage of the Parks’ material niceties without blowing their cover of forged professionalism.

But not all is as it seems. There are much more sinister events at play unfolding beneath the surface. The comedic tone set up in the film’s first act changes by the second and third act to manic horror and the tragedy of class warfare.

The genius of “Parasite” is that it completely subverts what would be the easy method of having clear cut protagonists (the poor) and antagonists (the wealthy). We root for the Kims whenever they take advantage of the naive and pompous Parks, but are soon disturbed by the fact that the Kims oftentimes act just as entitled. There are no clear cut answers as to who is right or wrong, who acts as the titular “parasite” and who represents the host.

A recurring theme of the film is the idea of “crossing the line,” a subject that is brought up by Mr. Park (Lee Sun Gyun) when speaking to the Kim patriarch, Ki-taek (played brilliantly by South Korean veteran actor Song Kang-ho). Park praises Ki-taek, who has taken the role of his chauffeur, for “not crossing the line,” an offhand compliment that seems meaningless, but in reality dictates what Park sees as ideal in a worker. Instead of “crossing the line” and becoming familiar with them, he prefers to keep servants far away so that their presence is virtually invisible aside from their duties. Eat from the hand that feeds you but don’t look at its face. Mr. Park will realize too late that the line not only was crossed, but brutally erased.

The film’s unpredictable atmosphere is enhanced by cinematographer Hong Kyung-pyo’s still and creeping camerawork, allowing viewers to peer around corners and pace each corridor inside the Park’s mysterious and extravagant home while we follow the two families’ antics. From warm and relaxing lounges to cold and feverish fluorescent lighting, Hong’s ability to capture various aesthetic tones is captivating.

The soundtrack composed by Jeong Jae-il pairs exceptionally well with the cinematography and direction. Discordant strings cut and writhe through suspenseful scenes which greatly enhance the intensity of the film, while slow and isolated keys add a somber touch when necessary.

It is no surprise that “Parasite” won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival this year. Bong Joon-ho has managed to add a masterpiece to his already highly celebrated body of work, delivering the perfect semblance of mainstream entertainment and sophisticated complexity that delivers an intricate and universal look into class inequality, which, in this age of excessive greed, is needed now more than ever.

MPAA Rating: R for language, some violence and sexual content. Korean with English subtitles.