Inmates Tell Their Stores at Prison Creative Arts Project

Gallery

The Prison Creative Arts Project works to humanize inmates and tell their stories through an annual exhibition of artwork by Michigan prisoners.

In his piece “Reluctance,” Alvin, a Michigan inmate who contributed to this year’s exhibit, depicts a young girl reluctant to give up her toy to her father, not knowing a better one is in store. Alvin writes, “It is obvious that Dad has interrupted his little girl’s toy party, and has attempted to remove something near and dear to her. Completely unaware of the brand new toy, she is reluctant to release that old battered patched up one.” He adds, “This is a representation of my very own (now) adult daughter, who is reluctant to let go of resentment over how I’ve missed so much of her life due to bad decisions ending in almost 25 years in prison.”

Started in 1990, the PCAP has aimed to assist currently and previously incarcerated people by providing them with a variety of art programs, as well as providing education to the outside community. By providing these services, the PCAP is able to assist prisoners in assigning value to themselves outside of their incarceration status.

Some of the programming that PCAP offers for prisoners includes literary review, creative writing and art workshops inside the prisons, and the Linkage Project a special arts program for those returning home from incarceration. They also run a podcast featuring previously incarcerated people, called “While We Were Away,” who speak about their struggles in finding housing and employment, to how they’ve changed.

However, one of the more major projects the PCAP offers is an annual exhibition of art by prisoners across Michigan. Now in its 24th year, it was started in 1996 by retired University of Michigan professor Janie Paul and her husband, Buzz Alexander, who both had already been involved with the PCAP.

This year, from March 20 to April 3, the PCAP featured 670 works of art from 26 MDOC facilities at the University of Michigan’s Duderstadt Center.

Ashley Lucas, current director of the program, said she was inspired to participate because, when she was 15 years old, her father was incarcerated and spent 20 years in the Texas prison system. “I now try to do for others what I wish someone had done for my father while he was incarcerated,” she says.

A lot of work goes into finding the artists. Lucas explained that, being in their 24th year, they have already established an extensive mailing list within the Michigan Department of Corrections. The project sends out a newsletter to the incarcerated people who are signed up for the newsletter three times a year, and put out a call for submissions in the summer.

“It takes the entire semester for teams of PCAP faculty, staff, students, formerly incarcerated artists, and professional curators to visit all 26 MDOC facilities where we meet with all who would like to submit work to our exhibition for that year,” she says.

After that, they begin to comb through the submissions. “We meet with the artists, give them feedback on their work, and select the best of it to enter into the exhibition,” Lucas says. Over 2,000 works were submitted this past year, and 670 were ultimately displayed at the Duderstadt Center.

The exhibition allows prisoners to have a creative outlet, and to proudly display their work to the public. “Overall, they are eager to participate, to have a conduit to communicate with the world outside and to prove how capable and creative they are,” Lucas says. “Many are really excited to receive feedback from the outside world, from our curation team, the art students who write critique letters to them, and the patrons in the gallery who write notes to them in our guest book.”

Lucas stresses that PCAP makes no profit from the exhibition: “All sales money goes directly back to the artists who made the work, except the taxes charged by the state and the prison.” It costs over $50,000 per year to put on the show, which is raised primarily through grants and private donations. Last year, the program was able to sell half of the 630 pieces that were displayed, earning approximately $26,000 for the artists.

Lucas says the program has a profound effect on the artists who participate. The participants “can define themselves by something besides their incarceration,” she says. “Think of what it means for a person to be able to call herself an artist as opposed to an inmate.”

Not only does it allow the artists to express themselves, it also gives family members a spot to gather and connect. It gives them “a place and occasion to meet one another, celebrate their loved ones, and show others the beauty of the people we often cannot see because the state keeps them hidden from us,” Lucas says.

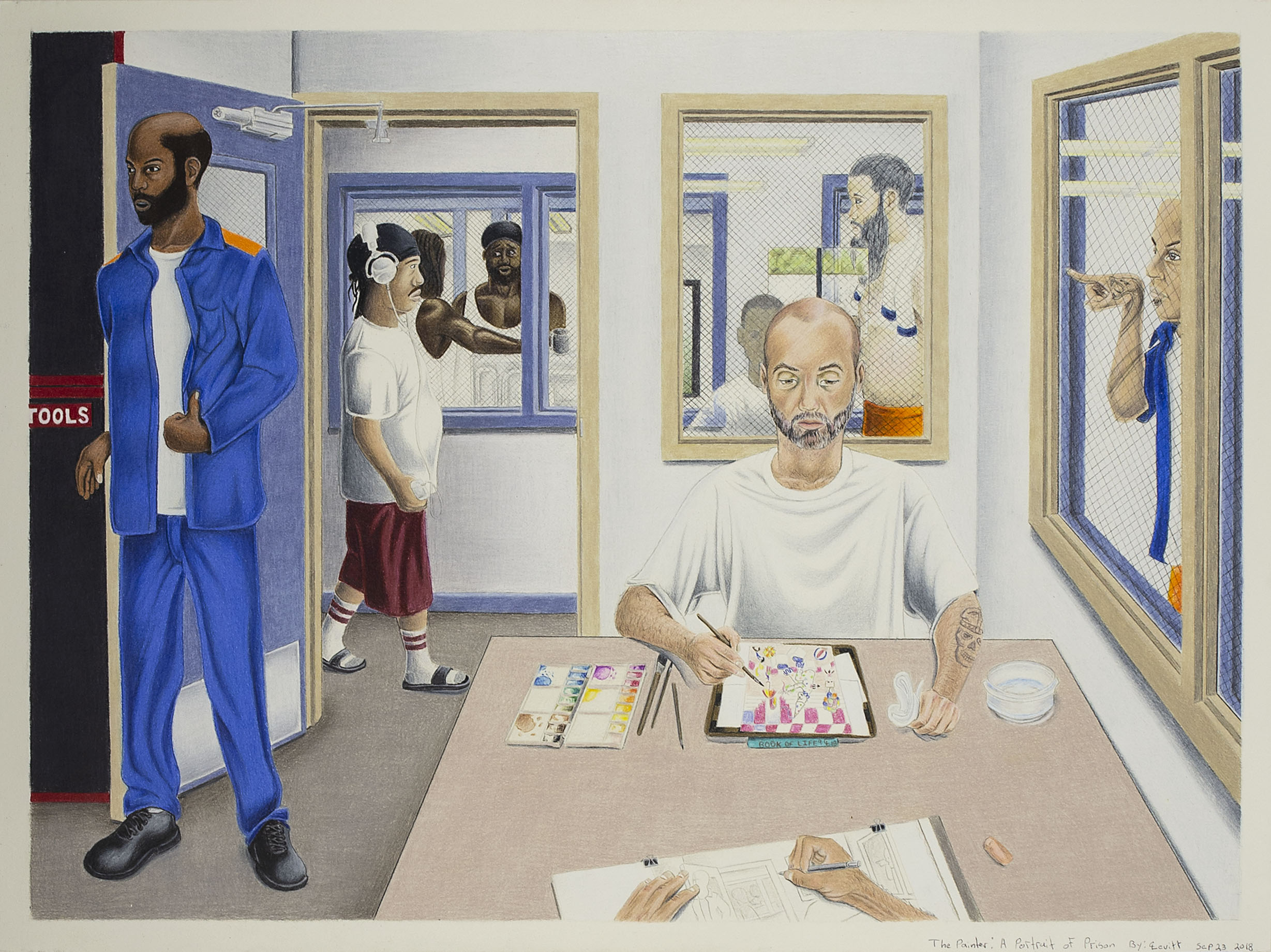

Participants showcase a wide variety of art styles, including watercolor paintings, sculptures, and pencil sketches. The theme of the artwork ranges from political in nature—like “Pipeline” by Yusef Qualls-El, a drawing depicting the school-to-prison pipeline—to commentary on prison life, like “The Painter” by Christopher A. Levitt—to self-portraits—like Amanda Van Valkenburgh’s vibrant and colorful “Happy!”

The program also allows artists to provide personal statements, which visitors can read at the showing. This allows for the artists to share their thoughts and ideas with others. In addition, it provides an eye-opening and sometimes heartbreaking look into the artists’ lives.

Many of the artists use this as an opportunity to express how meaningful being able to share their art is to them. “With prison locking down my body, art frees my mind,” one artist named Andrew Krease writes. “I can’t go and do most things I would like to do, but I can explore my own mind. Art allows me to share these adventures with others.” Others use it to express their frustrations with the things they are missing out on in the world. Another artist, Shu Jin, drew a sketch of her two nieces—”two more people in an ever growing list of new family members I’ve never met,” she writes—adding that, since the prison no longer allows them to receive photos, she will be unlikely to see much of them for several years. “We never really consider all the extra stuff that comes with a prison sentence, even if the extra stuff hurts the worst.”

Viewers can discover inspiration from the prisoner’s artwork and their artist statements. Christopher A. Levitt writes, “Whenever I hold a color pencil in my hand I feel a sense of ease and awareness when there previously was none.”

Lucas also pointed out the impact on the University’s students and visitors of the exhibition. “Many people make a broad variety of assumptions about who people in prison are, what their motives might be, and what kinds of art they might create,” she says. “The diversity, depth, and richness of our exhibition explodes those assumptions and invites the public to see the artists as complex individuals with much to contribute.”