Hope Has Not Left the Station: Detroit’s Beloved Depot Gets a New Life

Gallery

Detroiters celebrate as headlines confirm what they’ve already known deep in their hearts. Theirs is a city worth investing in. A city in which to take pride. Detroit is a city to call home. The long abandoned Michigan Central Train Station, whose glorious ruins have cast wistful, shadowy reminders of what once was from high above the Corktown skyline, is set to experience a rebirth. “The American second chance,” said Matthew Moroun, son of Manuel “Matty” Moroun, owner of the station since 1992. Maroun may be better known as the owner of the Ambassador Bridge.

Reporters were met in front of the historic building last Monday to hear confirmation of rumors circulating since March. “The Ford Motor Company’s Blue Oval will adorn the building,” Moroun told the crowd with satisfaction. “The deal is complete. The next steward of the building is the right one for its future. The Depot will become a shiny symbol of Detroit’s progress and its success.”

For the past three decades, the Depot has been a salient reminder of the great rise and devastating fall of Detroit’s economy. The last train pulled away from the station in 1988, after Amtrak and Conrail downsized to smaller locations. What was once a major public transportation hub had become obsolete in the automotive capital of the world, and the building was left to be ravaged by the elements and stripped by scavengers. The car industry would eventually allow for much of Detroit’s population and commerce to abandon the city for suburbs. The automaker’s return is expected to attract young talent in technology and innovation, offering a competitive urban environment in which to explore the future of electric and autonomous vehicles. While the community sits tight for an unveiling of plans from Ford, expected June 19, memories of life at the train station stir.

Pat Springstead, co-owner of Nemo’s Bar on Michigan Avenue looks back. “My dad had a bar over on 22nd and Bagley (Foss’s) when I was a young person, and I used to work there, helping him out, cleaning things up and that. That was back in the late ‘50s, so I have a vivid memory of the train station when it was up and running. I mean it was a grandiose building,” he describes. “It was one of those buildings that you would walk in the entrance way and literally, it would kind of take your breath away. So to see it in disrepair for all those years was disappointing. But now that it seems pretty obvious that Ford motor car company is gonna come in and take it over, it’s pretty exciting.”

Springstead is significantly pleased that it is Ford behind the wheel of big change in the the neighborhood and city. He once owned a restaurant in the Renaissance Center in the 300 Tower that Ford occupied at the time. Springstead says he would see Henry Ford II, who had an office on the top floor, as well as his brother William Clay Ford, best known for his controlling interest in the Detroit Lions football team.

“So knowing the train station, and being down with Ford in the Renaissance Center for 17 years and seeing Ford come back to the city again, I just think it’s terrific,” he says.“The train station for some reason has always been a symbol of the degradation of Detroit to some degree and the fact that that particular building will not be torn down, but be refurbished and brought back to its past glory, we’ll say is great symbolism.” Springstead adds, “For everything that Dan Gilbert’s done, and obviously he’s been the straw that stirred the drink for us, bought all the buildings, invested in all these things, so he really got it going, but this, for all the wonderful things he did, this symbol will be even above that. To the rest of the country, to the rest of the world, that Detroit is obviously back in business.”

Corktown has been seeing the resurgence for some time now of people coming to the city who hadn’t for years, from restaurant goers to the aforesaid Ford Motor Company, who recently opened its new site, The Factory, at the corner of Rosa Parks and Michigan. “We’re excited to choose this inspirational location in one of Detroit’s resurgent neighborhoods to accelerate our work on electric and autonomous vehicles,” Jim Hackett, Ford president and CEO says in a press release. The 45,000 sq ft. building is part of what is expected to be a Ford campus in Corktown, culminating with the train station.

“One of the really big things of Ford coming down to the train station,” Springstead continues, “is that Ford is asking the young millenials, the engineers and the computer science people, to be a part of Detroit. They want to be a part of the urban setting and be around things that are happening culturally. It’s revitalizing the younger generation a) to stay here and b) to come here. We’ve already seen people come from New York, Los Angeles, Chicago. They want to be a part of Detroit. It’s a good story, we can give a good job here, the cost of living is good compared to where they were living. So I think it’s just really terrific.”

Springstead says they’ve pretty much seen it all at Nemo’s since opening in 1965, three years before the Tigers won the 1968 World Series Championship just down the block. His dad, Nemo, lost his bar at 22nd and Bagley to the path of the I-75 freeway and purchased what would become a family run restaurant and neighborhood anchor. When the Tigers moved out of Corktown 20 years ago, Nemo’s started shuttling guests to sporting events and concert venues to stay connected to the crowds and the players.

Reminiscing about being inside the train station during his teenage years, Springstead says, “Back then, it was gleaming, with big round marble columns and high vaulted ceilings. Sometimes my mother would take us over just to look at it. It was really that kind of iconic building. Just really something special.”

Winston Williams, 88, of Northville and longtime resident of Detroit, also recalls the train station’s breathtaking splendour. “I was 18 years old,” he says of his first visit to the station the day he left home for the army. “The morning that we left was in May of 1948. Me and my mother got up and got dressed and we walked from our house to the Davison and caught a streetcar. I was living on the east side on Main Street between Joseph Campau and Dequindre off McNichols. We caught the streetcar to Michigan Ave and walked to the train station. It was a big place. To me, it looked kind of like a castle.”

The Michigan Central Station (MCS) was the tallest train station in the world in 1913 when it opened ahead of schedule, hours after a fire broke out in the old MCS located on the Riverfront. Its impressive 18-story office building loomed behind an ornate 3-story train depot whose Beaux-arts architecture, steeped in rich, historical detail, was designed by the same teams responsible for New York City’s Grand Central Station. Its lobby boasted design elements of ancient Roman bathhouses and was the pinnacle of wealth and opulence. Surrounded by low-level buildings and houses, the massive structure could be seen for miles. Yet the train station’s distance from downtown, coupled with the fact that it never had a compatible parking structure, proved to be real challenges over time. The year after it opened, Henry Ford would offer workers $5 a day and the mass production of automobiles would be the greatest obstacle of all for public transportation in Detroit.

The years surrounding World War II brought fresh hustle and bustle to the slowing station and many Detroiters still associate their visits there with that time frame. “When I boarded a train,” Williams recalls, “there were about 12 of us going to Fort Dix in Trenton, New Jersey for basic training. The car we left in was all black. At that time, it was rough. There weren’t too many jobs after the war. Most of the servicemen were coming back, they were gobbling up all the jobs. For a black guy, 18 years old, just out of high school, there really wasn’t much. It (enlisting in the army) was really the only thing that I could feel that I was able to do to work.” Doris White, 96, of Royal Oak, associates the MCS with wartime memories as well. She met her husband Bob for the first time at the Central Station when he arrived in Detroit on a military furlough. Theirs was an acquaintance of correspondence, he a serviceman in California in 1942 and later the Philippines, and she a “Rosie the Riveter” at a factory in Woodward Heights working a surface grinder, a vital cog in the defense industry of WWII. Doris had a girlfriend who dated a service mate of Bob’s and connected the two through letters. She recalls even now, as she finally met him in person outside that bustling hub, how “things started to spark.” The train station would unite them twice more during Bob’s furloughs, and on the third visit–about a year after meeting–Doris would board that train to California with her new husband, a fast-tracked union which would endure over 65 years.

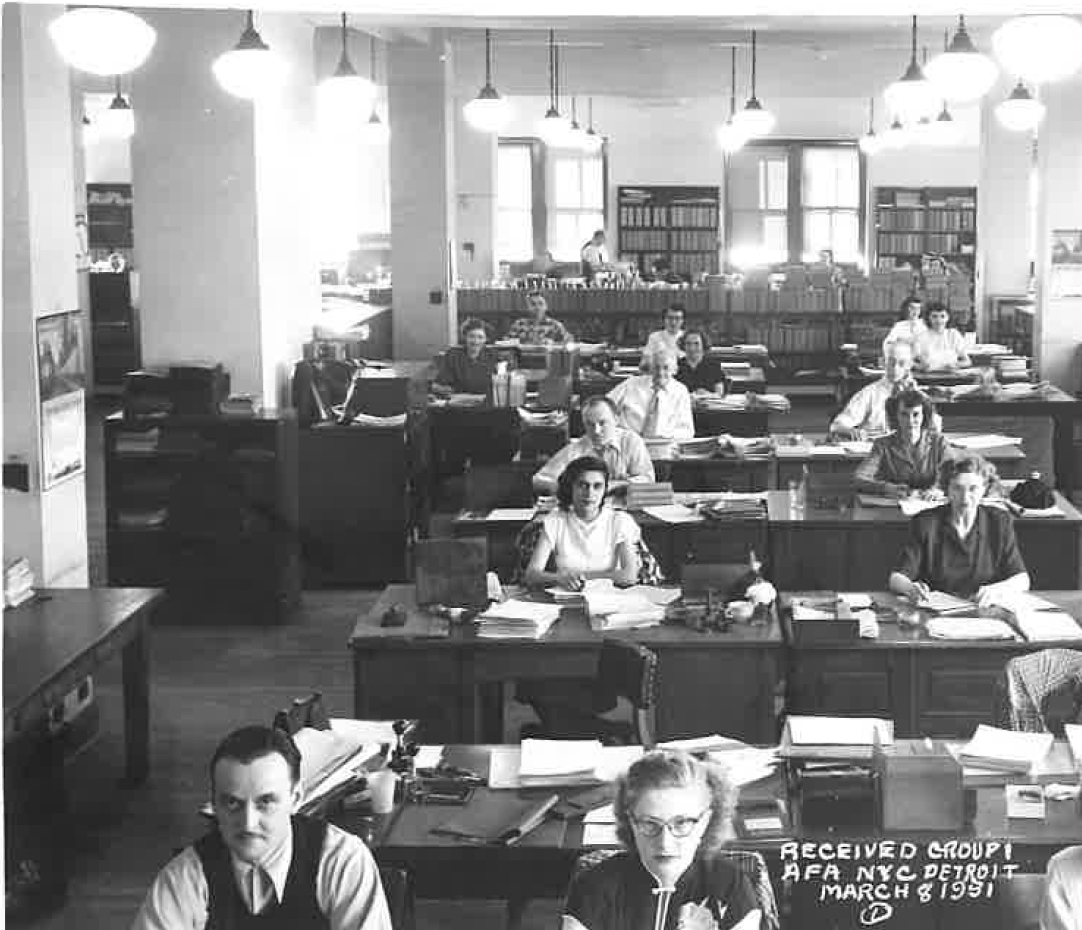

Susan McGraw, Professor of Telecommunication at Henry Ford College, speaks with pride of the many years her Aunt Loretta Brandt worked as a bookkeeper for Conrail Train Company inside the MCS. Brandt was also a committed member of the National Association of Railway Business Women, which formed in 1941 to stimulate interest in the railroad industry and met monthly to support women working with the rails. McGraw says that Brandt, who passed away in April at the age of 93, was given good opportunities of advancement in the railway business, which was rare for women, and remained at the station for over 40 years. Here she also met her husband, Don Brandt, who worked as a mailroom clerk. The couple were married over half a century.

Loretta Brandt remained in her position until Conrail closed its presence at the station and then she chose to retire rather than relocate to Philadelphia. In 1981, she picketed with co-workers to protest proposed cuts in the federally subsidized Amtrak rail system. McGraw says of her Aunt Loretta, “She was an inspiration to me, as I always admired her dressing up and going to work every day when I was a little girl, which was rare for that time frame. My mom was a stay-at-home homemaker and the mother of nine children. I always say that I had the best of both influences with my mom and her mothering skills and my aunt and her business career. I believe that these roles inspired me and my desire to balance being a parent and having a career at the same time, as both roles were very appealing to me.”

Local filmmaker Stephen McGee says the train station was the first place he brought his wife Cory when she came to visit him in Detroit in 2011. McGee, who had moved to the city in 2009, had connected deeply and immediately with its landscape and its residents. He threw himself into documenting stories of resilience, beauty, and hope which he saw all around him. McGee recalls clearly the night he picked Cory up from the airport and how they came and stood in the darkness, gazing up at the deserted depot tower from the lawn of the Imagination Station, a neighborhood nonprofit aimed to rescue and restore two 100+ year old homes on the edge of Roosevelt Park. McGee had been documenting the community project which lost its better half “Lefty,” alongside the old Roosevelt Hotel, to arson in 2012. Two years later the couple petitioned founder Jerry Paffendorf to allow them to move in to “Righty” with a goal to raise a family in the home and document their experience of renovation and life in Detroit. This renovation continues today, in a house 118 years old, where a family daily takes in the views of the 105-year old train station outside the front door.

“We love the train station,” Cory McGee says. “It’s so iconic in Detroit. It’s beautiful. You can see it from all over the city. We see people coming and taking their wedding photos in front of the train station every weekend, all kinds of tourists, hundreds and thousands of people coming and taking photos, filming, parking their cars in front of it. We watch all kinds of things every single day. It’s cool. It’s an incredible place.”

In regard to the new Ford deal Cory says,“It will be different, thousands of vehicles daily.” She adds, “It will be cool though. Because of all those people, there will be new businesses created as well. The only thing I’m cautious about is the traffic,” she explains. “Otherwise, I couldn’t be more thrilled that it’s Ford. It’s an existing company that has a great reputation. That’s the only way it’s going to get revitalized. We can’t sit on a vacant city and hold back. The fact that they bought this building,” she points to the nearby former DPS book depository, “and that building and all the surrounding buildings, it’s exciting.”

Bill Kelly, director of New Life Rescue Mission located along Michigan Avenue, also believes that these types of changes are positive for the neighborhood. Because of the development over the last 3-5 years, now Detroit police show up when he calls them. “For years no one ever showed up,” Kelly says of the family-operated mission that has been caring for men in the community down the street from the train station for over 50 years.

“For the most part, I don’t see much changing in the attitudes in Corktown,” he says. “There has always been some who are against seeing the homeless, but they are the minority. Others are very generous.” Kelly says the mission has been approached over the years to sell their building but inquiries have moved on. The aging property has many challenges but he doubts whether a move that would cause them to be more visible would ever be truly embraced. In regards to increased commerce in the area, this doesn’t change Kelly’s mission. City development and rising costs of living only reinforce the importance of organizations who shepherd those whose lives haven’t been easy.

With a character uniquely its own, the Michigan Central Train Station looms large in the memories of those who knew it full of life and those who have held in fascination its deserted beauty. It captured the first glimpse of the city for many who came searching for opportunity and adventure and it stands out still to those who follow, willing to roll up their sleeves to find both. The news of its revival as a historically preserved treasure that will adorn and uplift Detroit’s oldest neighborhood fills residents and business owners with joy. Though it is not yet clear how exactly the company will use the Depot, it has acquired enough goodwill from locals to believe its presence will be beneficial. Though Ford may not have been the first down the track when it came to believing and investing again in the Motor City, having the station restored will be a signal to all that Detroit’s renaissance is full steam ahead.