How Safe is Your Water?

With Gov. Snyder announcing in March that Flint water levels are safe enough for the state to discontinue its program to provide bottled water to Flint residents, many might believe the crisis is over. Yet it will take years for Flint to change its lead pipes and even after replacing all of them, that will not eliminate the risk for lead exposure. For officials to claim the crises is over may be good for public relations, but municipal water operators can make lead exposure much worse if they are not meticulous awith their work.

Due to the crisis in Flint, many communities in Michigan are making long term plans to replace old lead pipes that connect several homes to water sources. Detroit is ripping up roads and replacing old sewers and water mains, searching for any lead pipes they had not discovered before. This is a long and lengthy process and it may take years to find all the grimy lead filled pipes. Sections of the pipes are being replaced with copper, but not the entire pipe. The city can only replace the part of the pipes they own, the other part of the pipe is leading into private property which they cannot work on.

With plans of new pipes, there is also talk about the city handing out filters as was done in Flint. Detroit hopes this will lower the chances of lead exposure due to doing partial replacements throughout the city. Most lead pipes are not a shock to people whose homes date back to the 1930s, but they can’t help but wonder about how long they should be filtering their water: two months, ten months, maybe two years?

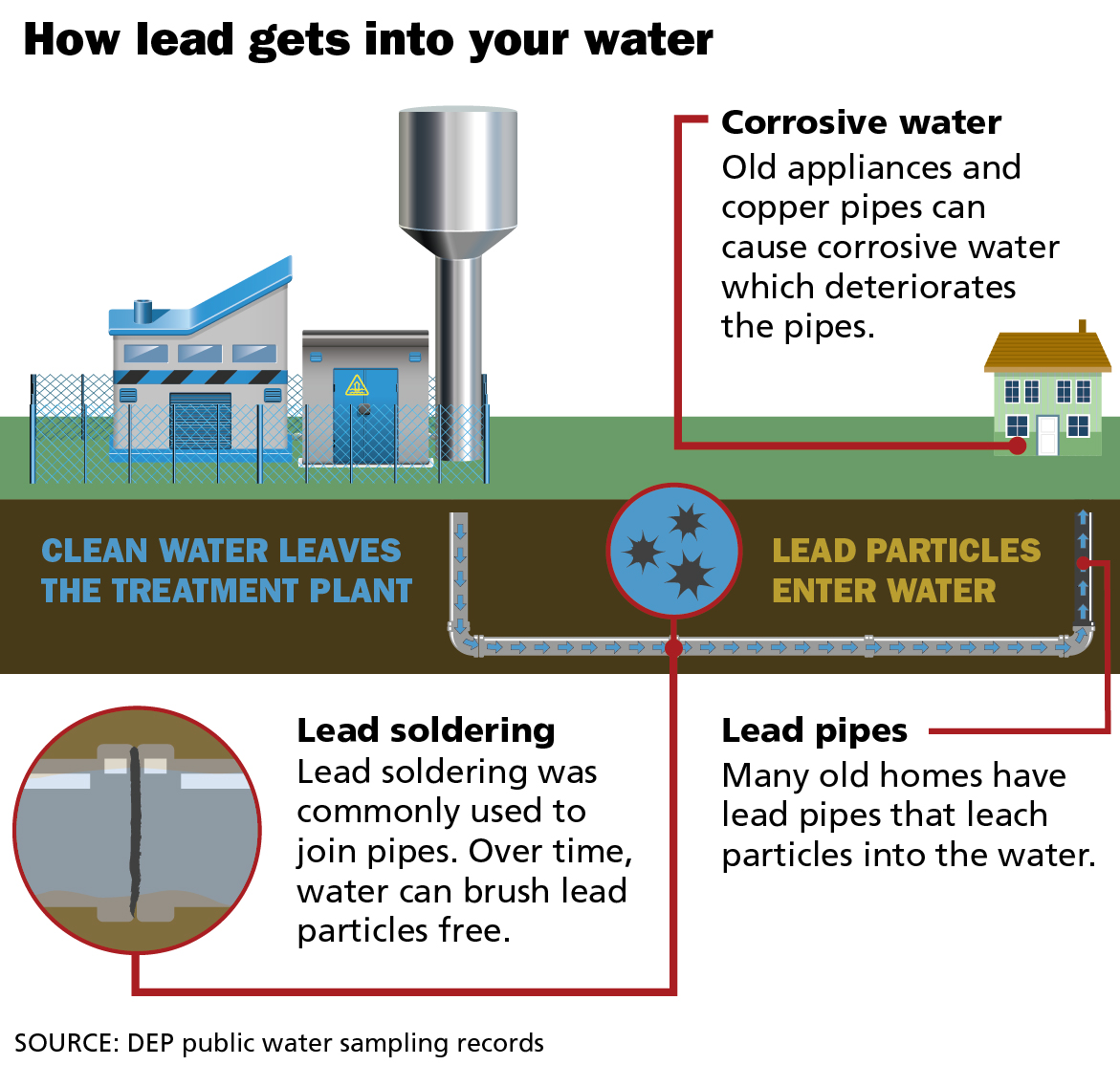

Replacing pipes involves risks. When the pipes are replaced, digging, hammering and all sort of objects are hitting the pipes at a fast rate and with tons of force. The force often flakes off pieces of lead into the tap water. The lead can either easily dissolve into the water without any notice or fall as big chunks into the water. Once the chunks break free it is hard to tell where they will end up on their journey. The lead can greatly impact anyone but have the greatest effect on pregnant women, people with weak immune systems, elderly and children. The partial pipes could possibly poison a whole family but in most cases water companies fail to mention the hazards.

Funding is an important question to ask, especially when Detroit can’t simply ignore the costs. Michigan Radio’s Lindsey Smith quoted deputy director of the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department Palencia Mobley, who estimates that Detroit has “between 100,000 and 125,000 lead lines in the ground – more than any other city in the state.” This could cost up to $500 million to replace every single lead pipe in the city of Detroit.

Not only are the costs a concern. The potential liability of doing the work raises worry. Often household owners blame work done outside their homes for problems in their homes, such as a crack in their ceilings even when the workers weren’t close enough to do that damage. Detroit doesn’t want to intrude on people and possibly cause bigger problems with the residents.

Partial lead pipe replacements continue to be performed in Detroit, and Mayor Duggan has instituted a program to try to warn and protect residents who are getting partial replacements. Dearborn is also conducting partial lead pipe replacements. Detroit and Dearborn have not come up with any further plans for getting rid of lead pipes and are continuing to take suggestions and meeting with water operations staff to fix the lead pipe issue throughout both cities.

Lead pipes may only be the start of the problems with regard to water quality that Michigan must address. In March, MLive reported that the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality found carcinogens perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl, substances known as PFAS, in water in New Baltimore, Mount Clemens and Ira Township. The MDEQ issued letters on March 2 declaring the levels do not pose any health risk. Environmental groups have requested more information.