HFC Academic Reorganization Faces Growing Pains

Gallery

This year marks the first year of Henry Ford College’s academic reorganization. Per the reorganization, HFC saw its campus’s six divisions converted into four schools: the School of Liberal Arts; the School of Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics; the School of Health and Human Services; and the School of Business, Entrepreneurship and Professional Development.

The goal of the reorganization, as stated by the administration, is to better connect departments in the college and to better promote student success. As Vice President of Academic Affairs Michael Nealon states on the College’s website, “Community colleges across the nation are now expected to provide the academic and career-based knowledge and skills to prepare students to thrive in our rapidly-changing global society. HFC must prepare them to become highly-skilled workers, meaningful contributors, and effective leaders in an ever-changing world full of emerging complexities and possibilities.”* By combining multiple departments into four schools, the college hopes to streamline communication between departments, providing them with a platform to stage discussions on how to better improve programs here at HFC.

The reorganization has seen the creation of new administrative roles, including the title of dean and faculty chair. This change marks a significant shift in the way HFC presents itself. The college has opted to adopt a more traditional administrative structure that many other academic institutions have implemented. Before this reorganization, each of the six divisions were headed by associate deans. While the role of associate dean still exists, both a dean and associate dean are assigned to oversee each school, and each department is managed by a faculty chair.

The reorganization has allowed the college to develop new programs for students. “We approved a whole new degree type in art. We established an associates in fine arts, which we didn’t have before. That gave us the ability to offer students a two-year program that would lead directly into a bachelor of fine arts,” says Angela Hathikhanavala, faculty chair for the Department of English, Literature, and Composition. Under the new structure, faculty chairs meet with the dean and associate dean once a month to review curriculum and try to improve upon current programs within each school. While net outcome of these meetings may not be very noticeable as of now, over time, this structure may facilitate new opportunities for students.

As of now, the re-organization’s effect on everyday student life is still unclear. This is not entirely unexpected however. Though the reorganization was centered on the goal of furthering student success, that is not something that can be achieved overnight. It will most likely be a while before significant impacts to students are felt.

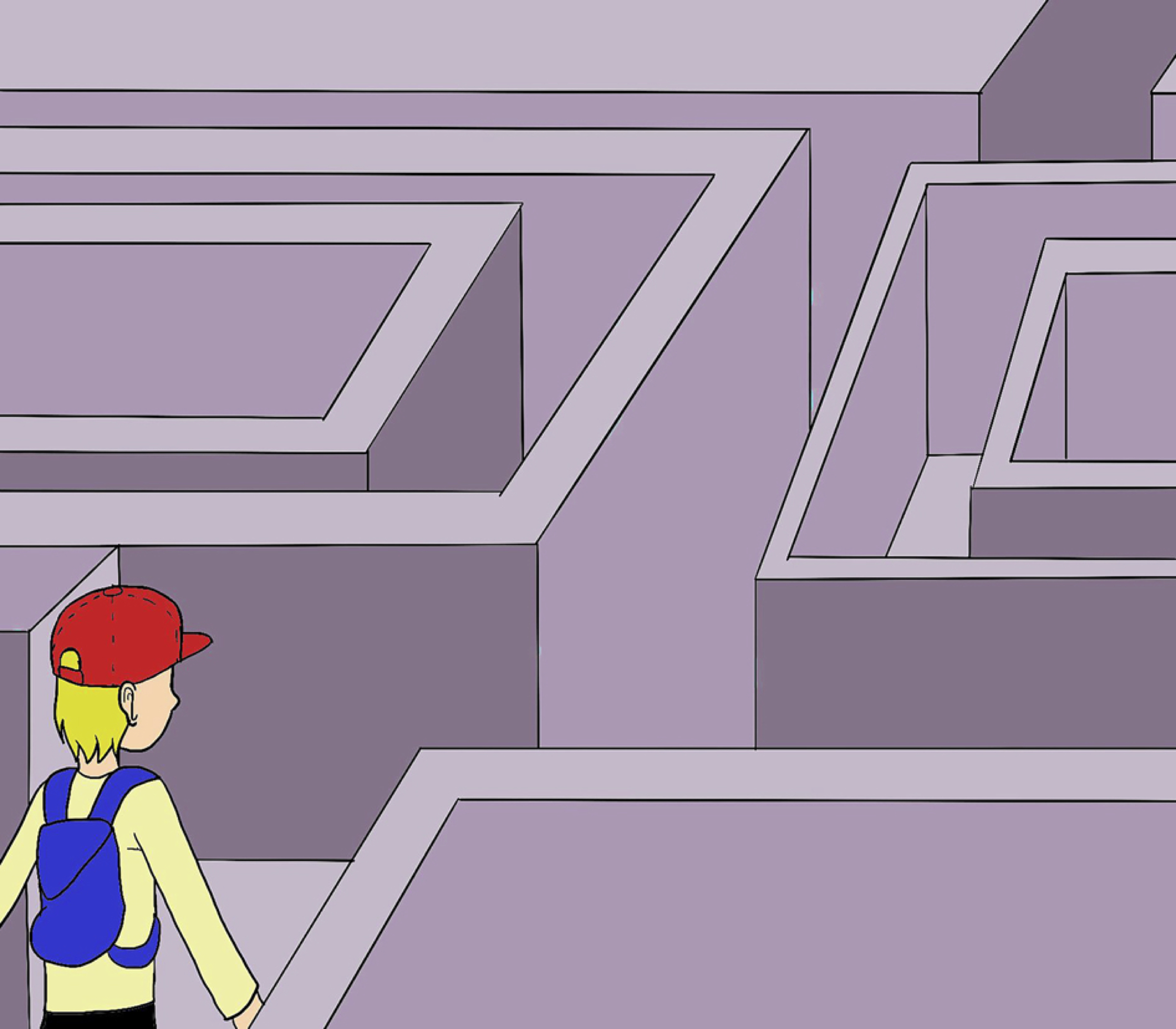

In the immediate aftermath of the reorganization, students may find it difficult to know where to seek help on campus or know where to go to seek assistance. This is due to the still unclear administrative roles following the reorganization.

Survey data collected from the College’s Senate-Administration Task Force on the Academic Reorganization, a task force assembled to identify complications that arose as a result of the reorganization, has found that despite the college’s focus on improving communication between departments, faculty and staff felt as though the reorganization had resulted in greater confusion between departments. When asked whether “college-wide communications have improved as a result of the academic reorganization,” only 19.1 percent of those polled agreed with the statement, while 34.6 percent disagreed. The remaining faculty and staff polled responded neutrally or shared no opinion. Among the key themes identified by the survey was that an increase in the levels of administration had “complicated communications,” and that the “same information is being sent from different people,” resulting in work being duplicated.

Some members of faculty feel as though the reorganization has resulted in increased bureaucracy. The additional levels of management have made it harder to navigate the administrative landscape to coordinate between departments, and to know where to go to carry out tasks and request information. This has led many to report feeling overworked and undermanned.

By bringing together so many departments under one roof, some believe it has made it harder to cultivate new ideas. While department-wide meetings have allowed for the development of new ideas, school-wide meetings currently function more like presentations and do not provide an effective platform to discuss possible changes. Former Faculty Senate Chair Eric Rader echoed this sentiment, stating, “I liked it better when we were a part of a division which was smaller, and we could interact with each other more.”

Current Faculty Senate Chair Jeff Morford explained that while the current structure is one that is common amongst most institutions, HFC’s old “flatter” model may have allowed for a more responsive system. The six divisions of the old structure may have facilitated more interaction in the spaces between divisions than the four-school model introduced by this reorganization.

Rader, like many other faculty and staff, believes that the fast transition, between proposal and application, of the new structure played a major role in the management problems the college is currently facing.

The reorganization was proposed in April 2017 and took effect at the beginning of the College’s fiscal year, July 1. As a result of the short implementation time, faculty members feel as though they were given limited say in the reorganization. Only a month was given to allow faculty to analyze the outcome of the reorganization and determine what complications could arise as a result. While the end goal of streamlined interaction between departments would provide a definite benefit to the college, there was no clear reason given as to why the college needed to undergo immediate reorganization. Rader says, “There was no rationale behind doing it immediately.” A slower, more gradual transition may have allowed the college to be better equipped to address complications as they arose. Morford states, “If we would have given this six more months of thought, we could have anticipated three quarters of the hiccups that came up.”

Despite his criticisms, Rader points out that problems are inevitable when any system is abandoned in favor of a new structure. “You’re always going to have some problems that are going to come up, with any new structure, that you can’t anticipate.” The college may just be experiencing a period of “growing pains” due to the recent adoption of the new structure. Hathikhanavala is optimistic and believes that so long as grievances are addressed and problems are dealt with as they arise, much of the confusion surrounding the reorganization can be fixed over time.

Reorganizations are becoming more frequent at higher learning institutions, often claiming the need to streamline communication and create “synergy” between departments and campus groups. Many question whether this top down structure has any place in academia.

In an effort to increase graduation rates and move students into the workforce as soon as possible, schools around the country are being cautioned against creating a college conveyor belt. Timothy Pratt of The Atlantic reports, “under pressure to turn out more students, more quickly and for less money, and to tie graduates’ skills to workforce needs, higher-education institutions and policy makers have been busy reducing the number of required credits, giving credit for life experience, and cutting some courses, while putting others online.” Schools like the University of North Carolina and The University of Southern Maine have begun cutting areas of study that contain “low productive programs.” These areas include history, political science and even physics.

The Campaign for the Future of Education, a movement dedicated to ensuring the voices of faculty, staff and students are not overshadowed by administrators and politicians, has spoken out against reorganizations centered around efficiency. According to Pratt, “The group says the push for more efficiency in higher education often leads to lower quality, and that reforms are being rushed into practice without convincing evidence of their effectiveness.”

In many cases around the country, college reorganizations accept little faculty feedback. Peter Payette of Interlochen Public Radio reported that at Northwestern Michigan College, administration had chosen to consolidate the humanities and social science departments in order to cut costs and streamline operations. This change was brought about with no feedback from the faculty or staff. The lack of feedback from faculty led one instructor to comment, “This situation provides yet another illustration of how the faculty at NMC feel that this administration does not value them.”

The Senate-Administration Task Force on the Academic Reorganization is intended to address problems generated by the transition. The hope is that views from faculty, staff and students are taken into consideration as HFC welcomes its new president this spring.

*Note: Vice President of Academic Affairs Michael Nealon's office was contacted but was not able to respond in time for this story.