“Dark Money” in Michigan

Gallery

On April 15, the Detroit Free Press Film Festival featured the documentary, “Dark Money,” directed by Kimberly Reed, at the Emagine theatre in Novi, Michigan.

Reed explores Montana’s history with campaign finance laws following the 2010 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Citizens United v. the Federal Election Commission. Reversing long held restrictions on political spending, in a 5-4 decision, the Court ruled that government cannot prevent corporations or unions from spending money to support candidates provided the money is not given directly to campaigns.

The film begins with an examination of Montana’s “Berkley Pit,” a former copper mine ran by the Anaconda Copper Mining Company. The company was able to influence politicians to relax mining regulations to open the mine. Following its closure in 1982, the pit began to fill with groundwater, which eventually became toxic, leading to concerns over the influence of corporate money in political campaigns.

Prior to the Citizens United ruling, which stated that the government may disallow the spending of corporations on political campaigns, Montana had some of the strictest campaign finance laws in the nation. In 1912, the Montana legislature banned corporate financing from political campaigns. Following the Citizens United ruling, however, much of Montana was inundated with TV and direct mail attack ads originating from organizations whose donors could not be traced. This is called “dark money,” a term that refers to funds given by undisclosed parties to nonprofit organizations that use those funds to influence political campaigns.

After the screening of “Dark Money,” the Detroit Free Press hosted a panel discussion. The guests included Paul Egan, Detroit Free Press reporter; Steve Linder, political consultant and fundraiser; and Craig Mauger, executive director of the Michigan Campaign Finance Network.

Linder was critical of the film, calling it a “conspiracy movie” that intentionally leaves out a lot of details. Linder, who argued for the allowance of undisclosed donations, said, “The Supreme Court of the United States has interpreted the Constitution to say we can assemble in any way that we want. We can form organizations that we want that have like-minded people and like-minded purposes.”

In response, Mauger cited a 2016 incident in which mailers praising Libertarian candidates were sent out to Republican voters a few weeks before the election. Mauger stated that it was suspected that the Democratic Party was behind the ads, although the actual source of the money was unknown. Mauger says this example shows how important disclosure is: “If you’re a Republican and you’re receiving a mailer that’s funded by Democrats, you might look at it differently than if you get a mailer funded by Republicans.”

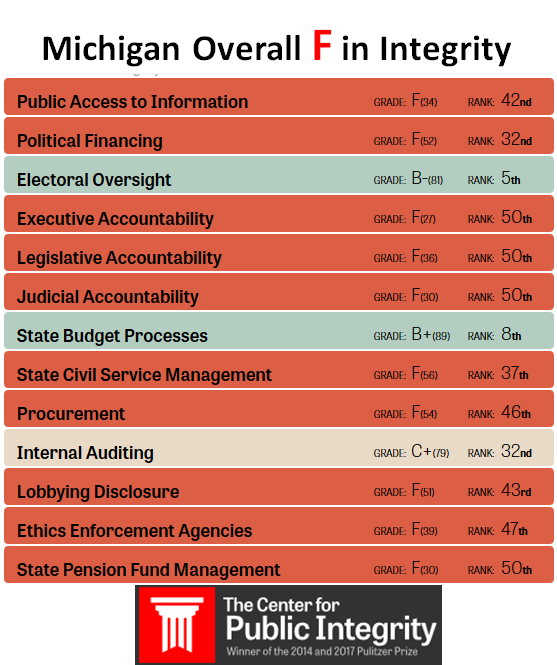

Paul Egan pointed out that Michigan has an “F” rating from the Center for Public Integrity, which puts out a semi-annual rating for how governments rate for disclosure and public ethics law: “There is an extreme lack of transparency in Michigan.” The Center for Public Integrity cites dark money as one of the reasons for this rating. Their website states that “Since 2000, state Supreme Court campaigns have been awash in nearly $40 million worth of television political advertisements, with the donors kept off the books.”