Why are Students Paying So Much for Textbooks?

Gallery

If you are a Henry Ford College student wondering why you had to drop $300-$800 on textbooks for your classes this semester, you are not alone in your outrage and confusion. At the semester’s beginning, we are all caught standing in the campus bookstore mumbling “What the…..?” It seems impossible that a glorified paperback can cost $168 and an online component destroys the budget completely. You may get lucky and find a cheaper copy of your textbook on Chegg Textbook or a rental option on Amazon, but with access codes and school specific editions, good luck.

According to a 2016-2017 survey of colleges conducted by College Board, an educational non-profit, the average two-year college student spends $1,390 per year on books and supplies, which is equivalent to 35 percent of tuition and fees at a community college. In 2016, “Covering the Cost,” a national Student Public Interest Research Group report showed that since 2006, college textbook prices have increased 73 percent - more than four times the rate of inflation. Today, individual textbooks often cost over $200, sometimes as high as $400. The study bases this result on two factors. In a regular market, competition drives prices down. In the textbook market, five major publishers control 80 percent of the market, locking competitors out. The second is that consumer choice rewards companies that compete on price and quality. In the textbook market, the student-as the consumer has no choice in the book assigned.

But what can we do about it? The HFC Eshleman Library staff is hoping to help answer that question by bringing attention to open educational resources. HFC librarian Tessa Betts explains, “These are teaching, learning, and researching resources that are publicly available, either because they are in the public domain or because the creators have given them a Creative Commons license that makes them publicly available.”

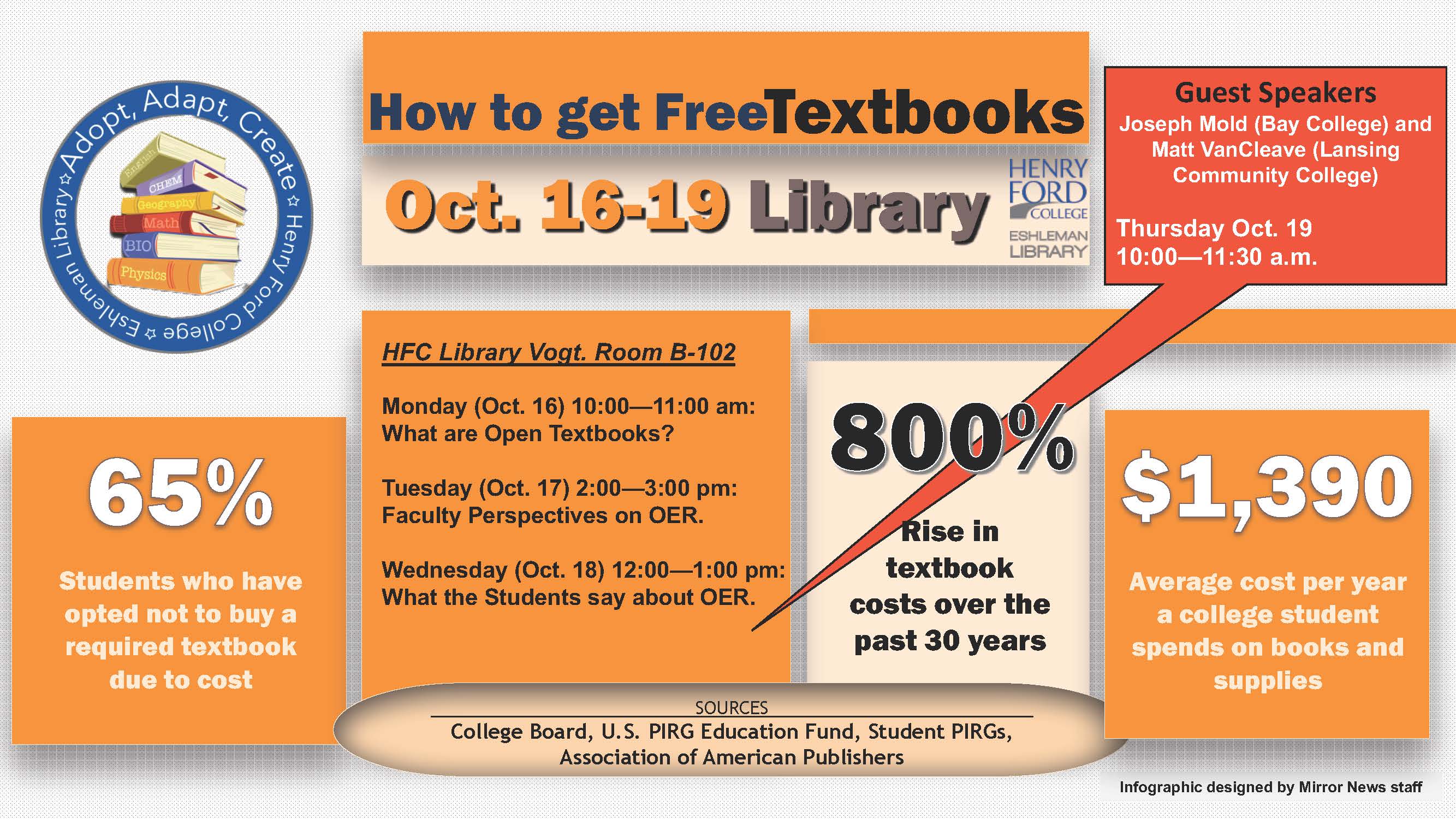

Betts continues, “Here at HFC, we are hosting this week long event (Oct. 16-19) in order to raise awareness and hopefully encourage faculty to adopt, adapt, or create their own open textbooks for classes. An open textbook is an OER, but it is specifically designed to take the place of traditional textbooks that can cost hundreds of dollars.”

Betts, who is passionate about helping students cut educational costs, is excited about the awareness week. She shows me an open textbook that she purchased titled, “Introduction to Sociology.” It’s a paperback with a simple cover, no frills, just the facts. It’s published by OpenStax, a non-profit education and technology initiative based at Rice University in Houston, and one of the major open educational resource providers. The goal of the initiative is “to encourage the sharing and reuse of educational content to improve educational outcomes.” Betts said she purchased the textbook on Amazon for $19.99 to have it as a model to show others. You can read the same sociology textbook online in a PDF file or download it to a Kindle completely free. Because it has a creative commons license, this entire book could be printed. Some colleges are offering to print open textbooks and charging students just for the materials. In this manner, a textbook can cost $20-$30. “That’s a tank of gas rather than a rent payment,” Betts points out.

The Student PIRG study claims that because the price of textbooks is far less than tuition and board, it has been deprioritized, and the power of textbook publishers has gone unchecked for decades. Yet these “smaller charges” can be the breaking point for students. The study reads, “At Morgan State University, in Baltimore, Maryland, a study showed that 10 percent of students dropping out for financial reasons owed the University less than $1000. That’s less than the amount the College Board recommends students budget for textbooks and course supplies for a single year.”

Across U.S. colleges, an average of 30 percent of students reported needing to use financial aid to cover books and many are having to add interest to inflated prices by using school loans to cover book costs. High textbook prices have hit community colleges the hardest, with 50 percent of community college students reporting the use of financial aid to cover assigned books.

The study concludes, “These numbers suggest that students are spending around $1.575 billion a semester, or $3.15 billion a year, in financial aid on textbooks. Therefore, alleviating high textbook costs could free $3.15 billion in state, federal, and local funding for use in reducing other higher education costs.This new data demonstrates that, in the broader context of increasing debt, high textbook prices are impactful enough to merit urgent, demonstrative action from policymakers on all levels to support alternatives to the traditional system of publishing.”

In 2013, the Student PIRG survey of 2,039 students from more than 150 different university campuses found that 65 percent of students had decided not to purchase textbooks because they were too expensive, and 94 percent of students who had chosen not to purchase assigned textbooks were concerned that doing so would hurt their grade in the class.

Nicole Allen, a spokeswoman for the Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition, voiced concerns to US News & World Report, “Whether it is doing worse in a course without access to the required textbook or taking longer to reach graduation, it is clear that the issue of textbook costs has evolved from a simple financial concern to a threat to student success. If the current system cannot provide every student with affordable access to the course materials they need, then we need a better system.” Though it has lightened physical loads, the transfer to digital platforms has not removed financial barriers for students. “Online access codes are the new face of the textbook monopoly,” said Ethan Senack, Higher Education Advocate at the Student PIRGs. An access code is a series of numbers that allow students to unlock learning software needed for their class. From here, students complete assignments, use study tools, and take quizzes and tests. According to the 2016 Student PIRG report, “Access Denied,” the average access code costs $100 by itself. It can also be found inside or bundled with a textbook, driving up the required cost. The code can only be used once and has a time limit, often of one semester. The report states, “Across institutions and majors, an average of 32 percent of courses included access codes among the required course materials. In bookstores, only 28 percent of access codes were offered in unbundled form. Even when acquired directly from the publisher, only 56 percent of all required access codes were offered without additional materials bundled in, despite federal law requiring materials to be sold separately.”

The report continues, “By making access codes single-use and individualized for each student, publishers eliminate a student’s ability to share with a friend, or borrow from the library if they don’t have the financial means to buy it. By creating access codes that include assignments and tests, publishers lock 100 percent of students in a course into buying their product and eliminate a student’s ability to opt-out. By transitioning to digital course materials, publishers now have the ability to eliminate excess supply that could lead to used book markets.”

Top publishers don’t view OER as a threat to their market, but with Amazon, one of the “Big 4” tech companies joining the OER movement, it’s visibility and influence is sure to grow. Amazon Inspire invites educators to discover, share, rate and review free educational resources, all with the simplicity of an Amazon account. It’s claim, “Amazon Inspire will help educators discover digital resources, benefit and learn from the work of their peers, and help improve the quality of education across the country.” It’s inevitable that the world’s largest online retailer has a plan to make a profit in this move, yet its high-profile status may propel forward a movement which brings large savings to students and educators. Sante Fe College, in Gainesville, Florida, reports to have saved students $1 million dollars in education costs since their professors have opted to use open educational resources. According to the College, during the Fall 2016 semester, there were 98 sections using an OER or “zero cost texts.” During Fall 2017, that number more than doubled with 207 sections.

Colleges are also beginning to offer “Z--degrees,” or “Zero-Degrees,” meaning that a student can follow a class plan and manage to graduate with a degree by taking only classes that have open textbooks. Currently Tidewater Community College in Virginia offers several Z-courses as well as a Z-Degree in Business Administration. This summer, Achieving the Dream, the national college reform network, announced an initiative to help 38 community colleges in 13 states develop new degree programs over the next three years using open educational resources. Michigan has one school in the enterprise, Bay College of Escanaba. According to ATD, this initiative “is designed to help remove financial roadblocks that can derail students’ progress and to spur other changes in teaching and learning and course design that will increase the likelihood of degree and certificate completion.”

David Wiley, an international expert on OER and Chief Academic Officer of Lumen Learning, a key partner in the initiative, says, “Colleges involved in the effort will need to integrate OER into their course redesign processes and update professional development to prepare instructors to use open, digital content most effectively. Over the next three years, colleges will create systems and structures that better connect curriculum and pedagogy to what students need to learn to be successful in academic disciplines and the workplace.” ATD says the $9.8 million in funding for the initiative comes from a consortium of investors that includes the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Great Lakes Higher Education Guaranty Corporation, the Shelter Hill Foundation, and the Speedwell Foundation.

At Lansing Community College (LCC), members of faculty, administration and the school board have joined together in the effort. According to an article by Jean Dimeo in “Inside Higher Ed,” besides expanding OER in general education courses, LCC is close to offering its first zero-textbook-cost associate degree in psychology. “There is interest from the president and board that we do more,” said Richard Prystowsky, LCC’s provost. “They see the great work we are doing … and want to ramp it up exponentially.” LCC has 15,000 students and offers about 1,150 courses per academic year. The college’s goal is to have 70 of its 700 instructors (125 full time and the rest adjuncts) using OER materials exclusively by 2018, and 70 percent of all instructors using OER by 2020.

In the article, librarian Regina Gong, who is heading the effort, said the goal is ambitious, but attainable. “Faculty really want to help their students,” she said. “They want to save their students money.”

This summer, California Gov. Jerry Brown signed $5 million into the California state budget for the development of zero-textbook-cost degree programs (or Z-Degrees). According to Andrew Rikard in Ed Surge, “The Z-Degree grant program empowers the chancellor of the California Community Colleges System to distribute grants of up to $200,000 to community college districts for each Z-Degree path developed. The system is the largest in the nation, serving over 2.1 million students at 113 community colleges. With the funds, districts will not only develop pathways to graduation using pre-existing OER, but can fund OER creation. The districts will also be required to package and publish their degree paths such that other community college districts in the California and beyond can borrow from their progress.”

In Michigan, interest in OER is growing. Last February, LCC hosted its second OER Summit. On Oct. 19, Joseph Mold (Bay College) and Matt VanCleave (LCC) will bring their insights about OER to HFC.