Civil Rights Art to Hip Hop: DIA Puts ‘67 Uprising in Context

Gallery

“Art of Rebellion: Black Art of the Civil Rights Movement,” at the Detroit Institute of Art, features art from the 1960s and 1970s that evoke a powerful and emotional message of black nonconformity and solidarity.

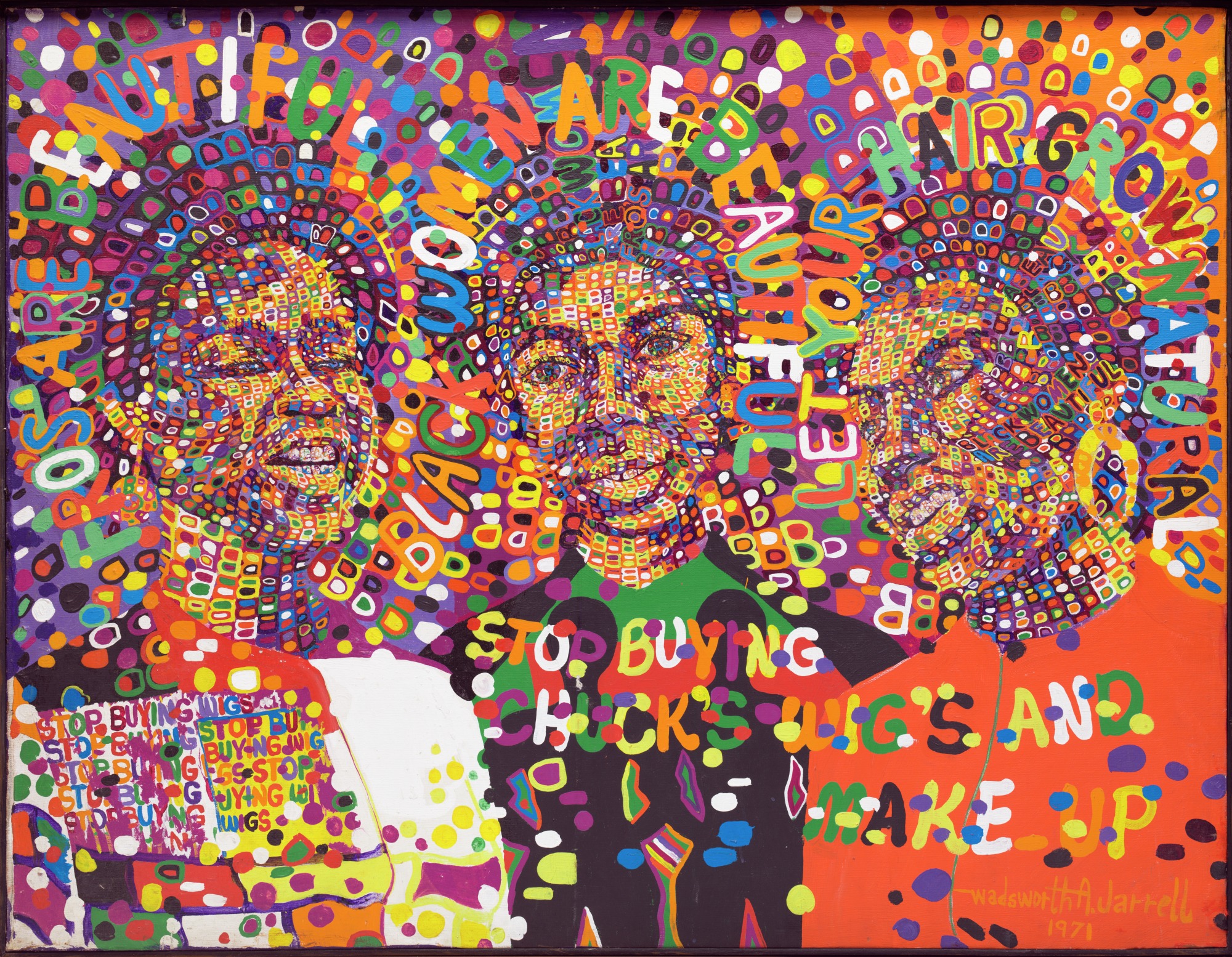

Black artists created art as acts of rebellion and as a portrayal of black identity and resilience. The exhibit explains the establishment of several African-American collectives during the Civil Rights Era, including the AfriCOBRA Artist Collective (1968, Chicago); the Kamoinge Collective – a collective of African-American photographers (1963); and the Weusi Artists’ Collective (1965, New York), among many others. These collectives show a movement determined to band together in the face of discrimination. The exhibit begins with Wadsworth Jerrell’s “Three Queens” - a vibrant and colorful painting of three African-American women juxtaposed with phrases such as, “Black women are beautiful,” and “Let your hair grow natural,” messages common to the “Black is Beautiful” movement, which aimed to subvert the idea that only white features and traits could be beautiful.

The Art of Rebellion exhibit ensures black women of the Civil Rights Movement are not forgotten. It features a photograph of Pat Evans, a model who shaved her head in protest of the fashion industry, taken by Anthony Barboza; a painting of Angela Davis titled, “Revolutionary” by Wadsworth Jerrell, and, most notably, a poster designed by Antonia Clifford for Blood at the Root – a Chicago exhibition that focuses on state violence against black women and girls. The painting of Angela Davis positions the words “Say Her Name” in the background and the names of black women and girls killed by police in the forefront. The #SayHerName movement has gained popularity in the black community due to a widespread feeling by women of color that black women are often left out of “Black Lives Matter.”

The exhibit’s centerpiece focuses on the 1967 Detroit uprising. During the summer of 1967, police raided an after-hours, unlicensed bar in Detroit on 12th and Clairmount Street - a predominantly black neighborhood. Tensions built up from years of racial discrimination and segregation burst, and a rebellion began. The conflict lasted about a week, and ended only after President Lyndon Johnson called in U.S. Army Troops. The aftermath was devastating - 43 people were killed; 33 were black. The 1967 rebellion was a pivotal moment in the history of the Civil Rights Movement.

In the exhibit, a TV plays a 6-minute video that includes a clip of Martin Luther King, Jr. giving a speech in Grosse Pointe in 1968. King warns that uprisings will continue to occur as long as black voices are ignored. One painting is titled, “1967: Death in the Algiers Motel and Beyond,” by Rita Dickerson. The Algiers Motel incident occurred in Detroit on July 25, at the height of the ‘67 uprising. During this event, three unarmed black teenagers were shot and killed by police. The piece features the victims of the incident as well as names of black men who have been killed by police more recently, including Michael Brown, Philando Castile and Tamir Rice. Dickerson’s painting begs the question of whether things have actually gotten better for black citizens in America since 1967.

In the last room of the exhibit, there is a large mixed media installation, “Black Lives Matter.” Before they exit, patrons can fill out postcards that are outlined with “Remember / Say / Create / Act” and hang them from a wall challenging them with the words, “After seeing this exhibit, I will….” One patron wrote, I will remember “what our ancestors fought for,” and create “a space for inclusion, communication, diversity, and love for everyone.”

The photography exhibit, “D-Cyphered: Portraits by Jenny Risher,” celebrates the influence of hip-hop music in Detroit. Risher is a graduate of Detroit’s College for Creative Studies and author and publisher of the book, “Detroit Heart Soul.” Her photography reflects an authentic and personal love for the city and artists who contribute here. After searching Detroit’s museum archives and galleries and realizing that hip-hop music was underrepresented, Risher began contacting local artists in 2015 and requesting to take their photographs.

Some of the most notable and recognizable artists pictured in this exhibit include Eminem, Kid Rock, Insane Clown Posse, and J. Dilla. James Yancey, aka J. Dilla, who died in 2006, is pictured somewhat abstractly – Risher took a photograph of his mother, Maureen “Ma Dukes” Yancey holding a photograph of her son, while surrounded by artwork commemorating him. J. Dilla achieved his claim to fame as a part of the group Slum Village and had worked with A Tribe Called Quest, Erykah Badu, and Busta Rhymes.

Risher’s exploration of the Detroit hip-hop music scene is fascinating. She juxtaposes influential artists and producers of this signature genre against famous Detroit landmarks. Don Was is pictured sitting on the stairs of the Fox Theatre, holding an album which he produced called “Flamethrower Rap” (1982) by the group Felix & Jarvis – the single of the same name is considered by many to be the first recorded hip-hop hit in Detroit. Another photo depicts the team of World One Records – one of Detroit’s first independent record labels – grouped together at the Ford Piquette Avenue Plant.

A photo of George Clinton has “the godfather of funk” pictured at the United Sound Studios, where he recorded many of his songs. Clinton was originally a staff songwriter for Motown Records and became one of the most influential record producers in Detroit’s history. Clinton continues to play frequent shows in the area with his band Parliament Funkadelic. Jeff Mills, commonly known as “The Wizard,” is also pictured. Mills was well-known for spending many nights in the 1980s playing new records. Risher explains that hip-hop music was underrepresented on other radio stations and that Mills “became the main conduit for Hip-Hop to reach Detroit listeners.” Risher’s photo “The Greatest Day in Detroit Hip-Hop” features Jerry Flynn Dale, who opened Def Sound Studios in 1985 – the first studio for recording hip-hop artists in Detroit. Risher’s photo is a reconstruction of Gordon Parks’ iconic “A Great Day in Hip-Hop, New York, 1988.”

Risher photographed artists at the Russell Industrial Center, a popular location for rap battles, and the backdrop to Eminem’s 2013 video, “Rap God.” She explains that “the mid-1990s Hip-Hop scene in Detroit was known for its battle-rap competitions.” Also included in the exhibit are Risher’s photographs of Saint Andrew’s Hall, the Marble Bar and the Michigan Theater, all popular current music venues, as well as United Sound Studios – the first independent and full-service recording studio in the nation. The DIA encourages patrons to share their thoughts of “D-Cyphered” as they did at “Art of Rebellion.” Guests can reflect on the importance of Detroit hip-hop locally, nationally, and personally. One patron wrote, Detroit hip-hop “saved my life,” and another wrote, hip hop “empowered black people.”

“Art of Rebellion” runs until Oct. 22 and “D-Cyphered” runs until Feb. 18. Both are free with general admission to the D.I.A.