Getting Race in "Get Out"

Gallery

Written and directed by comedian Jordan Peele, “Get Out” is no ordinary horror film. It is a creatively constructed harrowing yet satirical multi-layered piece of social commentary focusing on race relations in America.

The central character, Chris, is a young black man in an interracial relationship with a white girl. Chris accompanies his girlfriend Rose on a weekend visit to her parents. He is unsure of how they would react to the fact that their daughter is dating a black man. Rose assures him that her parents are liberal and would welcome him with open arms.

Upon arrival at the Armitage’s suburban home, Chris is welcomed and everything seems normal. Before long, however, he begins to notice strange things going on around him. His paranoia is justified as he is hauled into a living nightmare reflecting classic horror films like “Stepford Wives” and “Night of the Living Dead.”

As a platform for addressing race relations, “Get Out” stands out. The film puts into perspective a satirized yet disturbingly accurate presentation of historical as well as contemporary lived experiences of black people in America.

The title score, with lyrics in KiSwahili punctuated by a few English words, is a foreshadowing of what is to befall Chris. The words sikiliza kwa wahenga (listen to your ancestors) and kimbia (run), repeatedly chanted over an ominous sounding instrumental composition, reference slavery and the ties between the enslaved and their ancestors upon whom they would call for strength and guidance, and as a means of staying connected to the motherland.

The referencing to slavery is also seen in the odd behavior of Georgina and Walter, the black couple that work for the Armitage family. The two are considered part of the family. However, to Chris, they don’t quite fit in. Their subservience, and seeming indifference to his concerns about the Armitage family is suspect. Georgina and Walter bring to mind the skills that house slaves would employ in order to safeguard their standing with their masters in pre-emancipation America. They can also be seen as an allusion to the view that though slavery has long been abolished, the legacy of it still subjugates the progeny of the emancipated in mental bondage to this day.

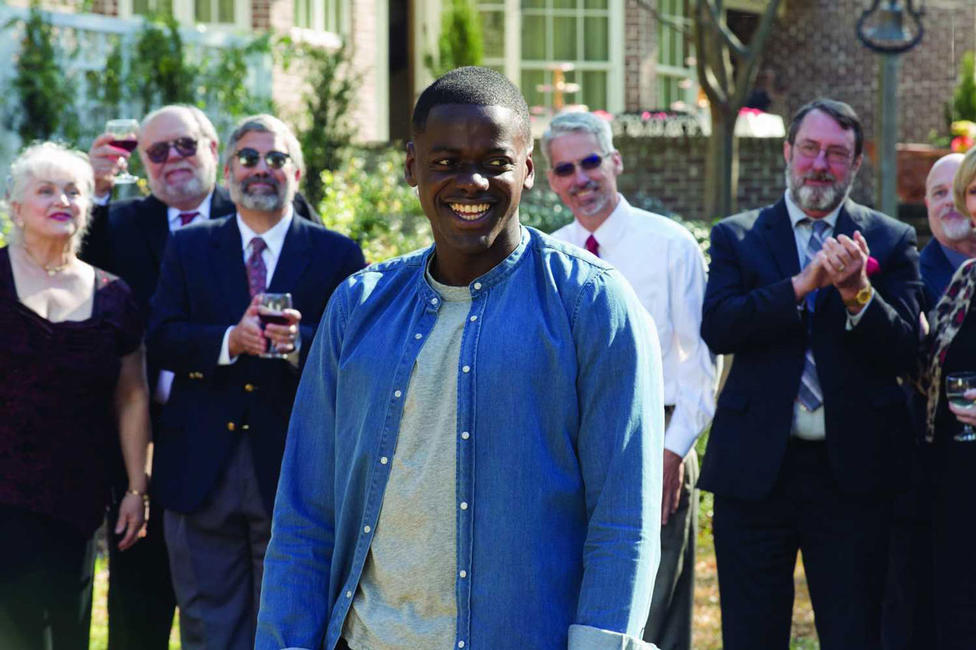

The Armitage family host a party at which guests are predominantly white. Logan, the only other African-American guest besides Chris, is a strange fellow. He is at the party with an older white woman who introduces herself as his wife. Aside from the color of his skin, there is nothing culturally black about Logan. He is a projection of the fear Chris has of what his own interracial relationship might turn him into. Logan’s character and how Chris views him also highlights the racial stereotyping: His choice of wardrobe is “white”; He does not respond as expected to a fist bump, which is considered a standard American “black” greeting; and when Chris seeks him, he does not display the comradery black people supposedly display when surrounded by white people.

Despite the seeming benevolence of the hosts and their guests, the liberal racism that underscores their strange gathering is disturbing. It is clear that they expect Chris to construe their objectification of him as a compliment to the black race. The party guests unashamedly “inspect” Chris as one would inspect a prized stallion highlighting the archaic notion that darker races are inferior and closer to animals and must therefore be treated as such. The silent auction that follows, where a framed image of Chris is the object on sale, is evocative of America’s pre-abolition slave auctions. In one scene, the protagonist literally has to pick cotton out of the armrests of a chair that he is tied to in order to save himself. This is symbolic of the need to reconcile oneself with one’s past in order to move forward in life.

Cognizant of past and current events across America, “Get Out” addresses the issue of black people disappearing from society never to be seen again as society carries on as if nothing has happened. It highlights the proliferation of appropriation beyond elements of culture. It is no longer enough to just simulate another culture, drastic measures are being taken to alter one’s physical characteristics to incorporate desirable traits of those of a different racial heritage.

The profiling of an individual by a law enforcement agent predicated on the color of his skin is also highlighted. Comparing how Rose reacts to the profiling of her boyfriend to how Chris himself reacts indicates how lived experiences contribute to our perception and reaction to situations. Chris’s resignation points towards attrition in relation to racial battle fatigue as experienced by people of color.

In the scene that sparked the #GetOutChallenge, Chris is outside the Armitage residence smoking a cigarette. Out of the darkness, Walter runs towards him. Walter almost knocks Chris over but turns in another direction at the very last minute and runs off into the darkness again. Chris is clearly disturbed by the sight of the the bulky Walter running towards him, but he just stands there and does nothing. It is not until towards the end of the film that the significance of the scene is understood. The underlying layer is that as oppression occurs, the oppressed bear witness yet lack the means or capabilities of changing the status quo. They sometimes internalize the oppressor and they themselves become tools of their own oppression.

As the film implies, what must be emphasized about watching it is that the viewers’ own lived experiences determines what they “get out” from the multiple layers that lie just beyond what we think we know about race.