The Media Landscape in Detroit: Then and Now

The 1960s were a time of rising social tension throughout The United States. Racial conflicts and anti-Vietnam War sentiments were especially high in Detroit. Many African Americans were frustrated with the racism, racial segregation and police brutality they faced living there. The city was riddled with Vietnam War protests, often resulting in mass arrests. Detroit’s minorities, however, still had no voice. Author Harvey Ovshinsky, who was inducted into the Michigan Journalism Hall of Fame in 2015, discussed the lack of balanced media coverage in Detroit in an interview with The Mirror News. According to him, during the 1960s “Black people were not existent [in the media] unless they were causing trouble” and “women, as well as women’s issues, [were] only covered on the society page.”

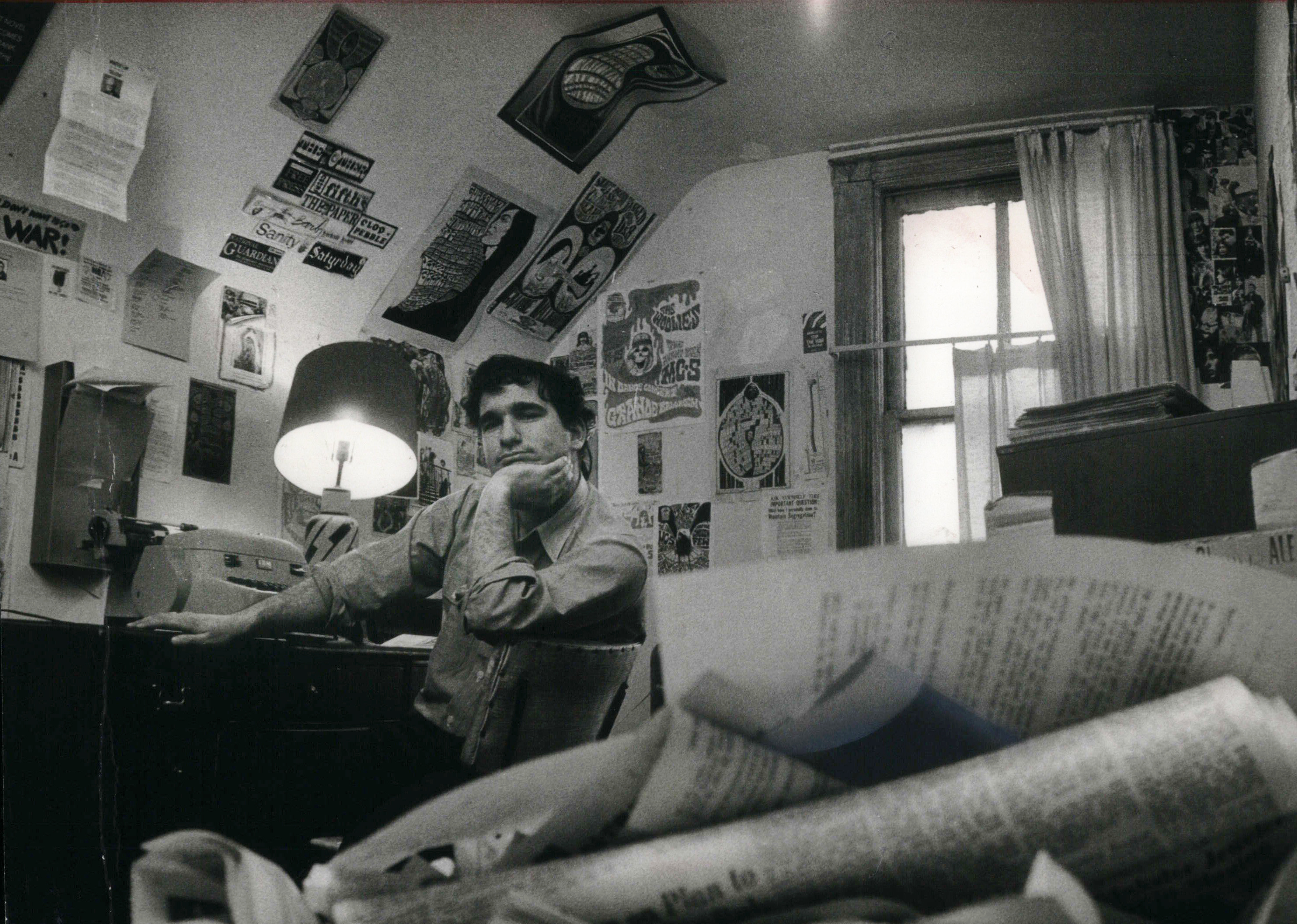

As a 17-year-old from Detroit, Ovshinsky visited Los Angeles and worked at the L.A. Free Press, the first underground newspaper in the United States. Inspired by his time at the underground paper, Ovshinsky returned to Detroit and in 1965 created “The Fifth Estate,” Detroit’s first underground newspaper. He described his initial efforts, and the response he received:

“I went door to door to all these civil rights and peace organizations telling people ‘hey look, you got any press releases? I want to write your story.’ At first no one knew what an underground newspaper was, and everyone was used to their press releases being shredded by The [Detroit] ‘Free’ Press. Eventually word got out and eventually people started reading the paper, and it just grew.” “The Fifth Estate” did grow, and at one point reached a circulation of 30,000. Not only did “The Fifth Estate” become more popular, but it sparked a liberal print revolution throughout Michigan. In Detroit itself, Wayne State University’s student paper was changed in 1967 from the Daily Collegian, which Ovshinsky described as “so boring, so conservative, so right-wing,” to “The South End,” a liberal paper giving a voice to the working class. Only two years later, another leftist underground newspaper was created: ”The Ann Arbor Argus,” which had connections to the White Panther Party, and Students for a Democratic Society. Finally, in 1977, Michael Moore created “The Flint Voice,” an underground alternative newspaper in Flint, Michigan. These papers, along with “The Fifth Estate,” created a liberal media presence both in Detroit and throughout the state of Michigan.

The 1960s were also the start of “engage journalism.” Engage journalists, as Ovshinsky explained, were journalists that didn’t just cover events but “were inside the demonstrations.” The practice of engage journalism brought added dangers to the job. During his time at “The Fifth Estate,” Ovshinsky said, “We had been tear gassed once or twice, threatened by the right wing, and the police were spying on us.” Despite the added dangers though, there was also a sense of fearlessness, “When you’re young you don’t think anything like that is going to happen. You feel like you can handle it. It was exhilarating. We were too young and arrogant for it to be scary. We were angry.” However, the Detroit riots of 1967, which resulted in forty-three deaths, were frightening even to engage journalists. Ovshinsky stated, “I was scared during the riots, when the trucks came down my block and the National Guard started shooting… those were crazy, rough times.”

Since the creation of the internet and cable news, print journalism has begun to dwindle, and some argue that journalism itself is going extinct. Ovshinsky, however, contends that journalism isn’t dying with print, but transforming: “That’s what cavemen said when they stopped writing things on walls and started writing things on parchment. We’re always going to need stories and we’re always going to want to hear the truth.” However he does worry about “the overkill of the 24/7 news cycle on cable television. It kills our intelligence. There’s just so much bullshit they have to fill up. It’s all entertainment.” As journalism transitioned into cable television, it seemed that only mainstream news was able to continue in Detroit. Both “The Ann Arbor Argus” and “The Flint Voice” have stopped printing, and there are no television broadcasts to take their place. “The South End” still exists, since it is funded by Wayne State University, but it has become more of a traditional campus newspaper. “The Fifth Estate” is perhaps the sole remaining liberal voice still publishing, but it is only a shadow of what it once was, running purely on volunteers.

Detroit in recent years has been going through a restoration period. New businesses and art galleries are popping up throughout the city. The media landscape of Detroit, however, is once again resembling the early 1960s: dominated by mainstream news, and not reflecting the views of many of its residents. Perhaps things are ripe for a new liberal media outlet in Detroit. As Ovshinsky and “The Fifth Estate” have shown, people want to know the truth, even if that truth might start a revolution.